July 4, 2024

News Release: Province must cancel coal leases if it’s serious about improving recreational experiences

The Alberta government has reopened Crescent Falls recreation area after investing to improve it, yet…

The Bighorn

The AWA is seeking legislated protection of the Bighorn as a Wildland Provincial Park as was promised by the provincial government in 1986.

|

|

The Bighorn is cherished for its cool, clean water running through gravel beds, wide open valleys, lush floodplains and unique mountain ranges. PHOTO: © H. Unger |

The Bighorn is home to a rich tapestry of life: elk, bighorn sheep and grizzly bears roam freely; harlequin ducks float down pristine streams which contain bull trout. The Bighorn contains critical headwaters, with river and streams flowing out of the Bighorn almost 90 percent of the water flow of the North Saskatchewan River (North Saskatchewan Watershed Alliance 2012). This provides water not only for Alberta’s capitol region, but for the Prairie Provinces downstream.

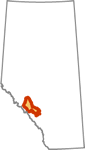

AWA’s Bighorn Area of Concern JPG PDF MAP: © AWA FILES

AWA’s Bighorn Area of Concern JPG PDF MAP: © AWA FILES

About a 3 hour drive from both Calgary and Edmonton, the Bighorn parallels the Continental Divide, extending from the Red Deer River in the South to the Brazeau River in the North. At 5,000 km2 the Bighorn fits neatly, like a missing jigsaw puzzle piece, into a gap of protected National Parks lands, where Banff and Jasper abut. In fact, much of the Bighorn was once included in the national parks nearly a hundred years ago. This protection was withdrawn during the First World War. It was again promised for protection by the provincial government in 1986 – a designation that never came to pass. The AWA is seeking legislated protection for the Bighorn as a Wildland Park as was promised by the Alberta government in 1986.

With the designation of the Bighorn Backcountry in late 2002, the Government created 6 Forest Land Use Zones (FLUZs), now Public Land Use Zones (PLUZs) that encompassed much of the Bighorn. The eastern boundary of the Bighorn contains unmanaged or “vacant” public lands which extend to Rocky Mountain House.

Immediately adjacent to Banff and Jasper National Parks, the Bighorn contains two small but strictly protected areas; the White Goat and the Siffleur Wilderness Areas, both established in 1961.

Much of the Bighorn has been divided into 6 Public Land Use Zones (PLUZ), which are established to help manage industrial, commercial, and recreational land uses and resources. While AWA generally supports the use of PLUZs to better manage public lands in Alberta; in the case of the Bighorn these have overridden the Eastern Slopes Policy (see below) by legalizing motorized access in the Prime Protection Zone.

The 6 PLUZs in the Bighorn are:

The White Goat and Siffleur Wilderness Areas are protected under the Wilderness Areas, Ecological Reserves, Natural Areas and Heritage Rangelands Act. The only other wilderness area in the province is the Ghost River Wilderness. This very stringent form of protection is indeed to preserve and protect natural heritage in order to provide a benchmark for pristine landscapes that have not been affected by humans. It does not permit any form of development or consumption (such as fishing or hunting) and access into Wilderness Areas is permitted by foot only.

Historically, the area was managed under the Eastern Slopes Policy and the Integrated Resource Plan (IRP). Under the Eastern Slopes Policy, the majority of the Bighorn was designated as a Prime Protection, “to preserve environmentally sensitive terrain and valuable aesthetic resources” or as Critical Wildlife “to protect wildlife populations by protecting habitat that is essential to those populations”. Within these zones, industrial development and OHV use are prohibited.

The eastern portion of the Bighorn was designated as Multiple Use, “to provide for the management and development of the full range of available resources, while meeting long term objectives for watershed management and environmental protection”. Within this zone industrial development and OHV use are permitted.

Map of IRP Zones within the Bighorn JPG | PDF MAP: © AWA

AWA is seeking legislated protection of the Bighorn as a Wildland Provincial Park as was promised by the provincial government in 1986. The fulfillment of this protection promise would – in essence – protect the PLUZs in the Bighorn as a single Wildland Provincial Park, with the exception of the Kiska/Wilson PLUZ. AWA reiterates the importance of continued protection of the White Goat and Siffleur Wilderness Areas, which together protect 1000 km2 of pristine wilderness.

Wildland Parks are “large, undeveloped areas where visitors can experience the beauty of unspoiled wilderness and the challenge of self-reliance.” The establishment of a Wildland Provincial Park in the Bighorn would mean:

Within the Kiska/Wilson PLUZ and adjacent public lands, AWA would support the establishment of Public Land Use Zones (PLUZs) and undertaking sub-regional planning initiatives, which would establish motorized and non-motorized trail systems and manage industrial development to a high standard in appropriate areas which protect critical bull trout spawning areas and other key conservation values.

The Bighorn Wildland is a 5000 km2 piece of public lands nestled in the gap between Jasper and Banff National Parks; extending from the Red Deer River in the South to the Brazeau River in the North. The Forestry Trunk Road lies to the east and Highway 11, the David Thompon Highway, bisects the area. The nearby communities of Caroline, Nordegg, Sundre and Rocky Mountain House serve as important gateways, servicing visitors of the Wildland.

AWA’s Bighorn Area of Concern: JPG PDF MAP: © AWA

The Bighorn contains critical headwaters, with river and streams flowing out of the Bighorn almost 90 percent of the water flow of the North Saskatchewan River (North Saskatchewan Watershed Alliance 2012). This provides water not only for Alberta’s capital region, with over 1 million residents in Edmonton alone, but for the Prairie Provinces downstream.

Most of the Bighorn Wildland is in the Front Ranges geological province of the Rocky Mountains, except for the Blackstone-Wapiabi area to the northeast and Panther Corners to the southeast, both of which are part of the Foothills geological province. The Front Ranges contain a series of thrust faulted slices, exposing platform wedge gray-weathering Middle and Upper Paleozoic carbonate rocks, and in the upper parts, Meozoic rocks of the clastic wedge. In the Main Ranges province, there are resistant Lower Paleozoic/Proterozoic rocks in broad, open folds underlain by nearly flat-lying thrust faults.

The valley bottoms within the Bighorn Wildland contain floodplains filled with gravels and saturated with water; these dynamic systems extend far beyond the river banks with rivers that move and change channels frequently. Described as the ‘ecological nexus’ of mountain landscapes, gravel floodplains are critical for native fish such as bull trout, aquatic insects, amphicians, vegetation (more than 60% of plant species occur here), and birds (accounting for 70% of species diversity) (Hauer et al. 2016). They are also critical migratory corridors for large mammals such as wolves, ungulates, and grizzly bears and will become critical climate change refugia in the future for many aquatic and terrestrial species (Hauer 2016).

The Bighorn contains areas which are of provincial and national significance. JPG PDF MAP: © AWA

The Bighorn is located largely within the Rocky Mountain Natural Region, but the eastern border also contains important Foothills, which are currently underrepresented in Alberta’s protected areas network. The Kootenay Plains and the Ya Ha Tinda Ranch contain Montane valleys which serve as valuable overwintering habitat for ungulate herds.

Natural subregions of the Bighorn JPG PDF MAP: © AWA

Alpine: moss campion, creeping beardtongue, mountain heathers, purple saxifrage, rock cress, double bladderwort, alpine wallflower, alpine poppies and nodding pink cling.

Subalpine: limber pines, Engelmann spruce, subalpine fir, larch, Englemann spruce, wintergreens, heart-leaved arnica, bunchberry, various species and colors of paintbrush, alpine forget-me-not, sweet vetch and bearberry shrubs.

From left to right: forget-me-not, bunchberry and creeping juniper. PHOTOS: ©AWA FILES

Montane: the Bighorn lost most of its Montane subregion when the Kootenay Plains were flooded to create the Big Horn Dam. What remains of this ecosystem, along the David Thompson Highway, in Panther Corners and at the Ya Ha Tinda Ranch contains rough fescue, California oat grass, June grass, several species of sedges, wild blue flax and pasture sagewort.

Foothills: spruce, balsam fir, lodgepole pine, alders, balsam poplars, willows, wolf willows, chokecherry, showy aster, wild lily of the valley, sweet bedstraw, sedges, calypso orchids, lady’s slippers, northern twayblade, rough fescue.

The Bighorn contains habitat that is of considerable important to elk and bighorn sheep. Wolverine, Rocky Mountain bighorn sheep, pikas, marmots, coyotes, wolf, moose and mountain goats can all be found within the Bighorn. Due to climate change, pikas have been rapidly disappearing from North America. Bird species include spruce grouse, boreal chickadee, boreal owls, yellow-rumped warblers, Wilson’s warbler, pygmy owls, and rare harlequin ducks.

From left to right: the pika, hoary marmot and elk are all found in the Bighorn. PHOTOS: © AWA FILES

The Bighorn historically contained bison as well as caribou herds that roamed between the Bighorn and Banff. The White Goat Wilderness Area still contains part of the range of the Brazeau Herd of southern mountain caribou.

Bull trout are provincially listed and COSEWIC assessed as threatened, protecting the Bighorn would protect habitat and provide cool waters for the relatively robust remaining populations in this area (Weaver 2017).

Grizzly bears are provincially listed as a threatened species in Alberta. The Bighorn contains habitat that is considered to be of very high conservation value for grizzly bears, with most of it located west of the Forestry Trunk Road (Weaver 2017).

The Bighorn has been consistently used by Indigenous Peoples since ice retreated about 10,000 years ago. Archaeologists have found signs of vision quest sites, burial sites, tool-making sites, mat lodges, rock art, and circular to horseshoe-shaped cairns.

Archeological digs in the vicinity of the Ya Ha Tinda Ranch in the upper Red Deer River valley and a survey of the Kootenay Plains suggests that the earliest nomadic people in the Bighorn Region were the Upper Kootenay, part of the Ktunaxa Nation, who made long and continuous use of these areas. The Kootenay people likely came in from the Columbia River through the Howse Pass, hunting bison overwintering in the Bighorn’s wide valleys.

The Rocky Mountain Nakoda’s oral history indicates they were the predominant people to have lived on the central eastern slopes of Alberta. They travelled in smaller groups in order to effectively forage and hunt in the Rocky Mountains and foothills. Unlike the prairie Nations, who depended on much larger bison herds, they depended on mountain game and vegetation. The nearby Big Horn Reserve is located within the region where the northern clans traditionally settled (Rocky Mountain Nakoda 2018).

As territorial boundaries were not definitive and fluctuated often, a number of other tribes also inhabited the region: the Peigan and the Blood, who joined to become part of the powerful Blackfoot Confederacy, were among these groups. The Sarcee people, now known as the Tsuu T’ina Nation near Calgary once occupied the upper North Saskatchewan River area and enjoyed a loose alliance with the Blackfoot.

The Bighorn is a popular destination for hiking, equestrian use, angling, paddling, hunting, and camping. More recently, the establishment of designated trails in the Prime Protection Zone has also introduced motorized recreation into the area.

The Bighorn is one of the only intact, largely roadless areas remaining in Alberta. As such, the proliferation of motorized access opportunities (industrial access roads, seismic lines, pipelines, transmission corridors, trails; a.k.a. linear access) constitutes one of the greatest threats to the survival of several species at risk in this region, including both land-based species like the grizzly and water-based species like the bull trout. The Alberta Grizzly Bear Recovery Plan 2008-2013 calls for management of linear access densities below 0.6km/km² in designated core grizzly habitat and 1.2 km/km² in remaining habitat. Bull trout are a threatened Alberta fish species that is sensitive to stream habitat degradation; permitting a road density of as little as 0.2 km/km2 can reduce the probability of bull trout occurrence by about 30%.

Industrial development and industrial scale logging are not permitted throughout much of the Public Land Use Zones in the Bighorn due to the Eastern Slopes Policy. Protection of these areas would provide assurance that these areas are protected from development in perpetuity.

Significant abuses of public lands have been documented on the eastern portions of the Wildland and on adjacent public lands with an incredible proliferation of roads, industrial development and industrial scale logging which is all utilized by motorized recreationists. In order to manage these impacts AWA would support the establishment of Public Land Use Zones (PLUZs) and undertaking sub-regional planning initiatives, which would establish motorized and non-motorized trail systems and manage industrial development to a high standard in appropriate areas which protect critical bull trout spawning areas and other key conservation values.

Documented effects of motorized trail systems in the Bighorn. PHOTOS: © AWA FILES

In 2003 AWA began what was envisaged to be 4-year recreation monitoring study to document the impacts of motorized recreation on designated trails within PLUZs, but which still continues to this day. AWA’s concerns and recommendations follow from this work:

1. Restrict motorized recreation in the Prime Protection and Critical Wildlife Zones, consistent with the intent of the original Eastern Slopes Policy. Additionally, there must be no motorized recreation in federally protected Critical Habitat for species at risk.

2. Establish permanent enforcement presence and action in backcountry areas.

3. Only permit motorized use on hard-packed, engineered trails that can support this use, and in non-sensitive watershed areas.

4. Ensure all non-designated trails are physically blocked and signed at the junction.

5. Ensure that stewardship programs to repair damaged trail sections are conducted by professional engineering and construction personnel with expertise in hydrology.

6. Address water quality and fisheries objectives by building crossing structures at every water crossing along designated trails.

7. Increase management responsiveness to changing trail conditions.

In general, the Bighorn is known and valued for being one of the last remaining areas of wilderness in the province and AWA maintains that it should remain that way. AWA believes highway-side regions are best left undeveloped. AWA is firmly opposed to any commercial development within Bighorn Wildland. Fixed roof structures of any kind, or associated “adventure tourism experiences” are not compatible with maintaining a wilderness landscape. There are many excellent opportunities for tourism development and support (gas stations, hotels, etc.) within Nordegg, Caroline, Sundre and Rocky Mountain House and these towns are ideally situated to serve as gateway communities.

AWA believes that the Bighorn is strongly positioned to provide low impact eco-tourism opportunities. Outfitting for hunters, anglers, mountaineers, geological surveyors, photographers and tourists has a long and respected history in the area. Outfitting and ecotourism businesses are locally owned and operated, with the bulk of the income circulating in the local communities. With appropriate protection and management strategies, places like the Bighorn can be maintained in a wilderness state and contribute to the economy and our well being.

AWA believes the Bighorn should continue to provide opportunities for hiking, equestrian use, angling, hunting, and camping.

June AWA staff meet with AEP Director Recreation Ecosystem & Land Management-South to review R11 plans for logging in Bighorn area. Potential harvesting would be specifically for habitat improvement, no reforestation. Specifically for wildlife, elk, grizzly. Some potential for prescribed burn. Prescribed burning will not happen in Kiska/Willson PLUZ. Would be very difficult to do prescribed burn without risk of it getting away.

In spring, the Bighorn proposal is not finalized by the provincial government, and following the 2019 provincial election, the new provincial government confirms it will not implement the Bighorn Country concept, but would rather return the management of Bighorn to the North Saskatchewan Regional Planning process.

In fall of 2018, the provincial government releases a proposal for Bighorn Country, which entails the protection of the core of the Bighorn wilderness under the designation of a Wildland Provincial Park, in addition to creating an extensive PLUZ east of the Forestry Trunk Road in order to help manage the impacts of multiple disturbances and developments on these public lands. AWA supports this proposal and participates in the public discourse by publishing information about the proposal on social media, producing fact sheets, speaking to the media, and writing to MLAs.

In March, the provincial government releases recommendations made by the North Saskatchewan Regional Plan Council in 2014. AWA provides a submission to the government, stating that the NSRAC recommendations fall short of the protection that is needed for the Bighorn Wildland and must include, at minimum, those areas promised for protection by the Alberta government since 1986.

In the Kiska/Wilson PLUZ and remaining public lands, AWA notes support for the establishment of Public Land Use Zones and undertaking sub regional planning initiatives to establish legislative limits on land uses including industrial activity and motorized recreation, while recognizing and protecting critical bull trout spawning areas and other key conservation values.

AWA conducts two trail monitoring trips during the course of the summer, noting that the government has officially closed the Canary Creek trail to summer OHV use due to unsustainable conditions.

AWA conducts maintenance work on the Bighorn Historic Trail in the Wapiabi and George Creek drainage, noting the need to conduct assessments for work needed on the remainder of the trail.

Two trips were conducted to monitor the Hummingbird trail system. The first, in July, is conducted following particularly dry seasons over the previous two years. Noticeable additional damage is observed along the entire portion of the rerouted Canary Trail, with portions of the trail continuing to slump. In August, following almost a month of consistent rainfall, AWA notes the Canary Creek trail had been closed on July 28. The trails which remained open had significant amounts of erosion damage and water on the trails.

AWA’s annual OHV monitoring trip notes sections of the trail along Canary Creek were rebuilt in 2014 under the Backcountry Trails Flood Rehabilitation Program (BTFRP). These sections were built to a high engineering standard, yet less than ten months later, these new sections were already suffering significant erosion and soil slumping.

In July, AWA prepares a submission on priorities for the North Saskatchewan Regional Plan, which included:

In January, various motorized trails in the Bighorn are closed and some re-routed due to flooding and trail erosion, including Job/ Cline, Upper Clearwater and Kiska Wilson.

AWA’s Bighorn Trail maintenance trip finds severe damage from the June flooding. Some portions of the trail are almost completely inaccessible and will need major work.

AWA’s trail monitoring trip finds more severe trail damage on the Canary Creek trails: “The cumulative effects of the floods, the erosion, and trails reconstruction have devastated the Canary Creek valley.” Much of the damage is from misguided and poorly-planned attempts to cut major new trails, which have been cut through the vegetation and riparian areas with little regard for anything other than short-term motorized access.

ESRD closes all trails in the Hummingbird FRA circuit – except the Onion Lake road – to motorized traffic until further notice, due to extreme trail erosion. AWA trip corroborates this erosion and accompanying damage to vegetation, streams and soil structure.

AWA conducts its annual maintenance trip on the Historic Bighorn Trail.

AWA releases a 2012 update to the Bighorn Wildland Recreation Monitoring Project, highlighting observations and measurements taken during the 2012 monitoring trips. This update reiterates AWA’s position that the trail network near the Hummingbird FRA is unsustainable, that OHV traffic is nevertheless increasing, and that ESRD should take action to close the trails permanently.

Three years after it was originally due, ESRD releases the Bighorn Access Management Plan “5 year” Implementation Review. The report provided to AWA is based on a review of current and past members of the steering and standing committee and states that members of the committee “garnered input from the larger groups they represent as users of the Bighorn area”. Regrettably AWA and its 40 years of efforts at maintaining trails as well as our trail and access management monitoring work for the past eight years, including our reports to the ESRD department, did not qualify to comment as part of the review.

In August, AWA staff spend four days backpacking in the Bighorn Wildland, within the Clearwater Ram FLUZ trail system. Staff observe extensive trail damage inflicted by unregulated OHV use. In response AWA writes to AB SRD to ask that government respond to unacceptable trail degradation, and close the most damaged trails to allow for recovery. AWA’s request for trail closure is denied, and any commitment to better manage and regulate trail use within the Bighorn is yet to be seen.

In July, during the annual summer maintenance trip to the Historic Bighorn Trail, an outfitter’s report directs the group north to the Chungo Creek section. It takes several days of concentrated work to cut out at least 80 trees across the trail and to nip out as many new trees threatening to choke the trail as possible. In 2010 approximately half of the entire trail is surveyed for problems and worked on.

AWA completes the Bighorn Wildland recreational trail monitoring project begun in 2003 and produces a final report, “Is the Access Management Plan Working? Monitoring Recreational Use in the Bighorn Backcountry”. The report details increased illegal use of trails with seven major findings and makes a strong case for the removal of motorized trails from the Prime Protection Zone. AWA meets with Alberta SRD Minister Ted Morton to present the findings of the report and discuss protection of Bighorn Wildland.

AWA releases its report titled “Recreational User Perceptions of the Bighorn: Land Management Values and Concerns, Present and Future.” Based on the recreational user survey AWA conducted during the summer of 2007, the report finds that both individuals and organizations listed wilderness values as their top priorities for the area. Based on the research, AWA made several recommendations within the report including the establishment of a Wildland Provincial Park and the immediate removal of motorized recreation within the areas identified as Prime Protection and Critical Wildlife Habitat by the Eastern Slopes Policy.

AWA begins a water quality study of the Panther River to measure the impacts of Alberta Tourism Recreation Lease developments on the river. Testing will continue through the summer and into the fall.

AWA joins Weyerhaeuser for a flyover of their Forest Management Area in the vicinity of the Bighorn. Discussion surrounds forestry practices that mimic natural disturbances such as wildfire.

AWA begins its summer field work in the Bighorn. This year will mark the fifth and final year of primary data collection for the Bighorn Wildland Recreational Trail Monitoring Project. Over the course of the summer, data will be downloaded from the eight traffic counters placed along a trail system for motorized and non-motorized recreation. As well, AWA will begin the long-term monitoring of identified damage “hot spots” to understand the long-term sustainability of the trails.

AWA begins conducting a recreational user survey in the Bighorn Wildland. AWA spends 11 days out actively surveying over the summer. 158 individuals and 22 organizations completed the survey.

AWA releases its final report on the Bighorn Wildland Recreational Trail Monitoring Project. The purpose of the project was to assess the efficacy of management in the area with respect to the objectives of Forest Land Use Zone (FLUZ) planning. After two years of monitoring the 76-km trail system of motorized and non-motorized trails in the Upper Clearwater-Ram FLUZ, the report highlights three main findings:

These three lines of evidence strongly suggest that current management in the Bighorn

Backcountry will not protect the environment from degradation caused by recreational impacts.

After local residents contact AWA with concerns over construction along the Panther River, AWA visits the area in the south of the Bighorn. AWA finds an unprecedented level of development on four Alberta Tourism Recreation Leases (ATRLs) that run along the river, offering year-round services such as lodging, RV parking, and horse boarding, all on public land and regardless of season. AWA documents development and notifies government of concerns.

AWA sends out four volunteers and nine horses for its annual maintenance trip on the Bighorn Historic Trail. After flooding in July and September of 2005 halted last year’s efforts, volunteers expected to find considerable trail erosion and deadfall this year. Fortunately, this was not the case. The crew documented signs of increasing human impact at the camps along the trail such as the installation of plastic tarp toilets and showers, larger fire rings and the clearing of trees.

AWA releases its 2006 Trail Report for the Bighorn Historic Trail. The Trail Report details maintenance activities carried out by the trail crew and reports on the condition of the trail, including impacts such as erosion and deadfall. It also includes details of findings about the camps along the trail.

AWA staff conservationists continue trail monitoring activities in the Upper Clearwater/Ram FLUZ. Discouraging results of significant damage is found in areas where erosion problems have been exacerbated by off road vehicle activity. Signage and efforts by SRD to close off some areas are noted. In general, trail conditions suggest activity cannot be sustained.

AWA meets with the Minister of Community Development to discuss, among other items, designation of of the Bighorn as a Wildland Park in celebration of Alberta’s centennial year. The Minister states that while he wants Alberta’s parks to be the “lens through which the world sees Alberta,” his focus is to maintain existing parks rather than create new ones.

AWA raises concerns over proposed Firesmart and burn measures, as AWA believes they are being completed to preserve the forest economy and not for forest health. ALERT and AWA suggest the proposal allows an increase in the allowable cut of forests in R11 by 5% under the guise of managing wildfire and mountain pine beetle threats.

The Province cancels the land reservation for the development of the Abraham Glacier Wellness Resort. The Province will not accept any new applications for the area until the Whitegoat Lakes Development Concept Plan is completed. Suggested modifications to the Concept Plan include the establishment of a wildlife travel corridor, limits of small to medium sized accommodation, and the elimination of some discretionary uses, including the establishment of a heliport.

The 2005 Bighorn Historic Trail annual trail maintenance trip is cancelled due to record precipitation events during the spring and summer restricting access to the trail by destroying bridges, closing roads, and making riding the trail without damaging it an unacceptable risk.

AWA completes the 2005 interim report for its third season of field work on its Bighorn Wildland Recreation Monitoring Project. The interim report highlights the question of the sustainability of these recreation activities with respect to maintaining ecological integrity in the area. Key findings include:

The tenth anniversary of AWA’s stewardship of the Bighorn Historic Trail.

A proposal to develop the Abraham Glacier Mineral Spa and Resort in the Whitegoat Development Node is rejected by Clearwater County. The County of Clearwater Subdivision and Development Appeal Board (SDAB) denies the appeal for the development permit for the Abraham Glacier Wellness Resort.

AWA launches the inaugural season of the Bighorn Recreation and Impact Monitoring Program.

AWA publishes a new book, Bighorn Wildland, and begins a book tour through Alberta communities to educate Albertans about the Bighorn and conservation and to re-launch the Bighorn campaign.

AWA meets with the government and representatives to demand Wildland designation for the Bighorn and the prohibition of motorized and industrial access.

The Municipal Planning Commission of Clearwater County declines the application made by Icefield Helicopters (Rimrock Holdings Inc.) to increase their activity over sensitive areas of the Bighorn Wildland and the National Parks. Icefield Helicopters appeal Clearwater County’s decision to restrict their heli-tourism activity over sensitive areas of the Bighorn Wildland and the National Parks, however, Clearwater County upholds the original decision to deny an increase in activity by Icefield Helicopters over the Bighorn and National Parks.

AWA conducts an annual maintenance trip on the Historic Bighorn Trail.

AWA initiates public forums to discuss the future of the Bighorn Wildland.

AWA gives a presentation to Standing Policy Committee.

AWA declines to sign off on the Bighorn Access Management recommendations due to poor process.

Bighorn Backcountry Access Management Plan is endorsed by Alberta Cabinet. The Alberta Caucus approves Bighorn Access Management Plan which includes trails for motorized recreation in Prime Protection and Critical Wildland Zones, in violation of the Eastern Slopes Policy.

AWA conducts an annual maintenance trip on the Historic Bighorn Trail.

The government declares that the Bighorn Wildland is not protected and removes it from maps. AWA demands promised Bighorn Wildland Recreation Area be protected by legislation. AWA participates in Bighorn Access Management Advisory Group meetings.

The government establishes the “Bighorn Access Management Advisory Group” with the intention to develop a plan for access into the area.

Bighorn Country with protected core Bighorn Wildland formally presented to Alberta Government by conservation groups.

AWA undertakes extensive discussions with Talisman Energy Inc. and the EUB regarding drilling and pipeline plans for Bighorn Country.

AWA participates in the Alberta Forest Service – Friends of the West Country –Sunpine regular meetings in Rocky Mountain House.

The “Bighorn Country” Wildlands Coalition is established, with members consisting of provincial organizations, local citizens, outdoor recreationists, ecotourism operators, and guides and outfitters from the Sundre, Nordegg, Rocky Mountain House, and Red Deer areas. The Coalition’s goal is “to encourage the establishment of “Bighorn Country” as a means of ensuring the protection of this outstanding wildland for present and future generations while providing for heritage appreciate and a range of recreation and eco-tourism opportunities which are dependent on undeveloped, natural environments”.

In a report produced by the Alberta government titled “Parks and Protected Areas: Their Contribution to the Alberta Economy” finds that “on average, the economic contributions of parks and protected areas are comparable to those of other resource-based sectors”.

AWA adopts the Historical Bighorn trail through Alberta Land and Forest Services and leads a yearly trail maintenance initiative. Located in the Rocky-Clearwater Forest, the trail starts at Crescent Falls and goes to Wapiabi Gap and on to Blackstone Gap. In addition, AWA asks to adopt an extension of this trail, from the Blackstone, over the Chungo Gap to the FLUZ boundary on the east.

The Advisory Committee for Special Places 2000 released a report, which recommends that “areas already managed as wildlands, including Kakwa, Bighorn and Upper Elbow-Sheep, should be formally designated by the end of 1994”.

AWA conducts volunteer programs to clean all backcountry trails and camps of 60+ years of garbage.

In a letter to the AWA, the Minister of Tourism, Parks and Recreation states his belief that the Bighorn Wildland Recreation Area “could be legislated in a manner that would provide both an appropriate level of protection and facilitate opportunities such as hiking, cross-country skiing and equestrian use… It is our hope that imminent decisions will result in an opportunity for this positive strategy to get underway.”

The Minister of Forestry names the Bighorn Wildland Recreation Area and releases a park-like brochure about the area, including a map and regulations. A government publication includes the Bighorn as one of Alberta’s protected areas.

An Integrated Resource Plans (IRP) for the Bighorn is developed, designating much of the Bighorn as Prime Protection and Critical Wildlife Zones, prohibiting industrial development and off-highway vehicle (OHV) use.

Alberta government proposes establishment of David Thompson Country similar to Kananaskis Country, for the Bighorn Wildland.

A Policy for Resource Management of the Eastern Slopes (1977, revised 1984) designates most of the Bighorn as Prime Protection Zone, off-limits to industrial development and off-highway vehicle use.

The Alberta government promises a “minimum of 70 percent of the Eastern Slopes Region will be maintained in present natural or wilderness areas.”

The Environment Conservation Authority Report recommends emphasized protection of the natural values of the Eastern Slopes.

Province-wide public hearings for the Eastern Slopes include a review of the AWA’s proposed Wildland Recreation Areas, included is what the Alberta government later names the Bighorn Wildland Recreation Area.

The land entitlement of the Wesley Band takes effect, forming the Big Horn Reserve northeast of the Kootenay Plains near what is now the Abraham Reservoir.

The O’Chiese group, part of the Saulteaux Nation and the Sunchild of the Cree Nation from Saskatchewan arrive in the Bighorn after the second Louis Riel rebellion.

The rapid disappearance of the bison forces most First Nations into government-surveyed reserves.

The Bighorn is incorporated into Canada, and treaties are introduced.

David Thompson establishes a trading post at Rocky Mountain House and travels to the Kootenay Plains and across Howse Pass to briefly establish a new trading area in British Columbia.

David Thompson, one of the first Europeans to live in and write about the area, is sent to the area by the North West Company to establish a fur trade. He notes the Kootenay, Peigan and Blackfoot First Nations were all in the area.

The Bighorn has been consistently used since ice retreated about 10,000 years ago.

Archeological digs in the vicinity of the Ya Ha Tinda Ranch in the upper Red Deer River valley and a survey of the Kootenay Plains suggests that the earliest nomadic people in the Bighorn Region were the Upper Kootenay, part of the Ktunaxa Nation, who made long and continuous use of the Bighorn.

The Rocky Mountain Nakoda’s oral history indicates they were the predominant people to have lived on the central eastern slopes of Alberta. They travelled in smaller groups in order to effectively forage and hunt in the Rocky Mountains and foothills. The nearby Big Horn Reserve is located within the region where the northern clans traditionally settled (Rocky Mountain Nakoda 2018).

More recently, as territorial boundaries were not definitive and fluctuated often, a number of other tribes also inhabited the region: the Peigan and the Blood, who joined to become part of the powerful Blackfoot Confederacy, were among these groups. The Sarcee people, now known as the Tsuu T’ina Nation near Calgary once occupied the upper North Saskatchewan River area and enjoyed a loose alliance with the Blackfoot.

In 2003, AWA initiated a project called the Bighorn Recreation and Impact Monitoring Project. With the growing threat to landscape integrity from human use and the recent legislation legalizing motorized activity in the area, trail monitoring is crucial within the Bighorn Wildland. The project was designed to identify and assess the current status of recreational activity in the Wildland and document the local physical and environmental impacts that these recreational activities are having on the landscape. The study area covers approximately 110km of both motorized and non-motorized trails adjacent to the Hummingbird Public Lands Recreation Area (PLRA). Since 2003 AWA has performed annual trips to visually record and monitor the health of the landscape and ecosystems through which the trails run. We have also used TRAFx vehicle counters to record and analyze motorized vehicle traffic levels in this study area.

Significant trail erosion, where water captures and slumps trails during flooding events. PHOTO: © AWA FILES

Total monthly OHV counts from 2007 – 2015 in the Hummingbird PLRA. Green and blue lines show counts from the trailheads of year-round motorized trails. Yellow line shows counts from a trail permitted for equestrian and winter use only.

AWA is grateful for the support we receive from TRAFx Research Ltd. for our on-the-ground monitoring work in the Bighorn.

Since 2003 AWA has successfully used TRAFx vehicle counters to monitor motorized vehicle traffic levels in our study areas. Learn more about the TRAFx Vehicle and Off-Highway Vehicle Counters at http://www.trafx.net/.

AWA is also grateful for the support we received from ASRPWF for our 2012 on-the-ground monitoring work in the Bighorn.

July 4, 2024

The Alberta government has reopened Crescent Falls recreation area after investing to improve it, yet…

January 15, 2024

By Devon Earl Click here for a pdf copy. No amount of trail maintenance will…

July 31, 2023

AWA’s Bighorn Backcountry Report Alberta Wilderness Association has produced an important report that reveals there…

April 17, 2023

Wild Lands Advocate article by: Sean Nichols and Phillip Meintzer Click here for a pdf version…

September 15, 2022

Wild Lands Advocate article by: Devon Earl, AWA Conservation Specialist Click here for a pdf…

July 7, 2022

Wild Lands Advocate article by: Devon Earl, AWA Conservation Specialist Click here for a pdf…

June 1, 2019

Wild Lands Advocate article by: Joanna Skrajny, AWA Conservation Specialist Click here for a pdf…

March 1, 2019

By Vivian Pharis, AWA Emeritus Board Member Bizarrely this past fall, the possibility of Bighorn…

January 31, 2019

AWA has prepared a factsheet tackling some of the main questions we have seen surrounding…

December 19, 2018

On November 23rd, the Government of Alberta launched a consultation process on Bighorn Country. For…

December 1, 2018

Wild Lands Advocate editorial: by Christyann Olson Click here to download a pdf version of this…