Originating in the pristine wilderness of the Bighorn and a critical source of drinking water and wildlife habitat, the North Saskatchewan and Ram Rivers are under pressure from the cumulative impacts of industrial, municipal, recreational and agricultural use.

- •

- •

- •

AWA believes that expanding protection of the North Saskatchewan and Ram River corridors will help protect water, wildlife migratory corridors, and provide recreation opportunities including fishing, swimming, canoeing and camping.

- Introduction

- Features

- Concerns

- History

- Archive

- Other Areas

- 90 percent of 700 streams, lakes, and canals sampled in the agricultural areas of Alberta exceeded the phosphorous limits set by the Canadian Aquatic Guidelines. Excess phosphorus in surface water promotes eutrophication and excessive algal growth. The resulting decrease in oxygen can cause fish to die.

- Bacteria often exceeded water-quality guidelines.

The North Saskatchewan River valley provides important habitat for wildlife and is popular for recreation PHOTO: © AWA FILES

The North Saskatchewan and Ram Rivers originate in the Bighorn, with the two rivers joining upstream of Rocky Mountain House. From there the North Saskatchewan River travels north and west through landscapes which become increasingly developed, flowing through Alberta’s industrial heartland to the Saskatchewan border.

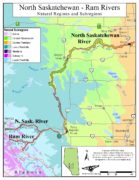

AWA’s North Saskatchewan-Ram Rivers Area of Concern. MAP: © AWA PNG PDF

The North Saskatchewan River provides a vital source drinking water for Alberta’s capital region, with over 1 million residents in Edmonton alone, as well as for Prairie Provinces downstream. The headwaters of the North Saskatchewan and Ram Rivers are largely located in the pristine wilderness of the Bighorn, which contributes almost 90 percent of the annual flow of the North Saskatchewan River (North Saskatchewan Watershed Alliance 2012).

The riparian corridors of the North Saskatchewan River also contain important Natural Regions including Foothills, Central Mixedwood, and Parkland, providing critical habitat and migratory corridors for wildlife. These three Natural Regions are all currently underrepresented in Alberta’s protected areas network.

AWA believes that expanding protection of the North Saskatchewan and Ram River corridors will help protect water, wildlife migratory corridors, and provide recreation opportunities including fishing, swimming, canoeing and camping.

Status

The North Saskatchewan and Ram River corridors are largely unprotected. The headwaters of the North Saskatchewan River are largely within the Green Area, with the river becoming increasingly surrounded by industrial development, private and settled lands as it flows downstream into the White Area (North Saskatchewan Watershed Alliance 2012).

Eagle Point Provincial Park and Blue Rapids Provincial Recreation Area (PRA) – Created in 2007, these two areas outside of Drayton Valley span 53 kilometers of the North Saskatchewan River and cover almost 5,600 ha of land in Boreal Dry Mixedwood and Central Mixedwood Natural Subregions.

There are also a handful of small natural areas which together encompass approximately 10 km2

Genesee Natural Area – 179.4 Ha

Burtonsville Island Natural Area – 328 Ha

Modeste Saskatchewan Natural Area – 388.9 Ha

Pembina Field Natural Area – 79.8 Ha

Mill Island Natural Area – 79.8 Ha

Management

Eagle Point Provincial Park and Blue Rapids Provincial Recreation Area were jointly established in 2007 in order to protect the riparian corridor and provide a core of non-motorized recreational opportunities within the Provincial Park and a designated trail system for off-highway vehicles (OHVs) within the Provincial Recreation Area. These two areas are co-operatively managed by the Eagle Point-Blue Rapids Parks Council.

Natural Areas are protected under the Wilderness Areas, Ecological Reserves, Natural Areas and Heritage Rangelands Act. They are intended to protect special and sensitive natural landscapes of local and regional significance, while providing opportunities for education, nature appreciation, and low-intensity recreation. These areas are typically quite small and include natural and near natural landscapes. New industrial development is not permitted (Alberta Parks 2017).

The Public Lands Act governs public lands, particularly as it pertains to watershed protection [S. 54 (1)] and the unauthorized usage of public lands [S. 47 (1)]. Other important regulatory mechanisms include the Forests Act [S. 10], and the Alberta Grizzly Bear Recovery Plan (2008).

Area

AWA’s North Saskatchewan and Ram River Area of Concern is 742 km2 in size. It begins east of the Bighorn Wildland and follows the river until the start of the industrial heartland at Devon.

AWA’s North Saskatchewan River Area of Concern MAP: © AWA FILES PNG PDF

Watershed

The North Saskatchewan River originates in the Bighorn Wildland and ends at its confluence with the South Saskatchewan River to form the Saskatchewan River.

Within AWA’s area of concern, the North Saskatchewan River Drainage is composed of five subwatersheds – the Cline, Ram, Brazeau, Clearwater and Modeste (North Saskatchewan Watershed Alliance 2012). The four headwaters subwatershed – Cline, Ram, Brazeau, and Clearwater provide almost 90 percent of the annual flow of the North Saskatchewan River (North Saskatchewan River Watershed Alliance 2012).

Geology

Information obtained from Boydell 1972 and Carlson 1971.

It is believed that the channel of the North Saskatchewan River was formed during glacial activity in the Pleistocene. As a result, the river corridors of the North Saskatchewan River contain alluvium (gravel) deposits surrounded by numerous glacial deposits of silt, clay, sand, and gravel that have formed features including sand dunes, outwash plains, and glacial lakes. The bedrock includes the Paskapoo and Brazeau formations.

Natural Regions

The riparian corridors of the North Saskatchewan River begins in the Foothills and flows downstream through Central Mixedwood and Central Parkland Natural Regions, providing critical habitat and migratory corridors for wildlife.

![]()

North Saskatchewan – Ram Rivers Natural Regions MAP: © AWA FILES JPG PDF

North Saskatchewan – Ram Rivers Natural Regions MAP: © AWA FILES JPG PDF

Vegetation

Foothills: spruce, balsam fir, lodgepole pine, alders, balsam poplars, willows, wolf willows, chokecherry, showy aster, wild lily of the valley, sweet bedstraw, sedges, calypso orchids, lady’s slippers, northern twayblade, rough fescue.

Central Mixedwood: Forests ranging from largely aspen dominated, transitioning to spruce in wetter regions. Trembling aspen, paper birch, Saskatoon, pin cherry, willows, low bus cranberry, northern bedstraw, Canada anemone, wild strawberry, golden rod, star step moss, big red stem moss.

Central Parkland: Aspen, balsam poplar, snowberry, bunchberry, chokecherry, pin cherry, dogwood, bracted honeysuckle, plains rough fescue. Native vegetation relatively rare in this subregion due to the extensive conversion to agricultural land and as a result, invasive species are common (Alberta Parks 2015).

Wildlife

Fish: lake sturgeon (provincially listed threatened, federally assessed as endangered), bull trout (provincially listed and federally assessed as threatened), northern pike, burbot, white and mountain sucker, walleye, sauger, and goldeneye

Birds: American kestrel, least flycatcher, pileated woodpecker, sandhill crane, great gray owl, northern pygmy owl, northern goshawk

Mammals: Canada lynx, cougar, black bear, grizzly bear, beaver, porcupine, muskrat

Cultural

The upper North Saskatchewan River corridor has been consistently used by Indigenous peoples since ice retreated about 10,000 years ago. Archeological evidence suggests that the earliest nomadic people in the area were the Upper Kootenay, part of the Ktunaxa Nation.

Over the past 500 and 200 years, respectively, the Assiniboine and Stoney Nakoda First Nations also moved into the region. More recently, as territorial boundaries were not definitive and fluctuated often, a number of other tribes also inhabited the region: the Peigan and the Blood, who joined to become part of the powerful Blackfoot Confederacy, were among these groups. The Sarcee people, now known as the Tsuu T’ina Nation near Calgary once occupied the upper North Saskatchewan River area and enjoyed a loose alliance with the Blackfoot.

There is also extensive archeological evidence of use along the North Saskatchewan River and watershed (Milholland 2015). The river was a major travelling corridor that allowed First Nations to trade with one another, and later became the major fur trading route.

Activities

The North Saskatchewan River corridor is a popular destination for hiking, equestrian use, angling, paddling, hunting, camping, and more recently, motorized recreation.

Cumulative Effects

Significant abuses of public lands surrounding the North Saskatchewan River have been documented, with an incredible proliferation of roads, industrial development and industrial scale logging which is all utilized by motorized recreationists. In order to manage these

impacts AWA would support the establishment of Public Land Use Zones (PLUZs) and undertaking sub-regional planning initiatives, which would establish motorized and non-motorized trail systems and manage industrial development to a high standard in appropriate areas which protect critical bull trout spawning areas and other key conservation values.

Dams

Dams have been known to have profound and highly site-specific effects upon river ecology. Hydroelectric reservoir dams are those which flood relatively large areas of land, allowing for the storage of large amounts of water. The water level in these reservoirs is regulated through dam operation, thus daily flow levels in the river channels can fluctuate widely over minutes or hours, creating ecosystems with no natural equivalent. Few aquatic organisms are able to adapt to survive these extreme, rapidly fluctuating flows. In addition, dams instantly block movements of fish that have patterns of long distance movement. For example, the North Saskatchewan River contains lake sturgeon which have been federally assessed as endangered. From their provincial Recovery Plan: “Severity and significance are also considered high, as dams can alter spawning habitats up and down stream, block upstream fish movement, and/or damage fish moving downstream (turbine mortality).”

Two hydroelectric dams, the Brazeau and Big Horn, already exist on the North Saskatchewan River. However, following flooding events in 2013, calls have once again been raised to build additional dams along the North Saskatchewan River, purportedly for flood mitigation. AWA is opposed to any future dam development along the North Saskatchewan River due to their known widespread negative impacts on river ecosystems.

Agriculture

Several studies conducted in the 1990s have indicated that agricultural practices are contributing to the degradation of surface water quality in Alberta and that the potential for impacts increases as agricultural intensity increases (Alberta Agriculture, Food and Rural Development 2000). These studies also showed the following results:

Wildlife

Critical habitat for threatened bull trout has been compromised by the extensive use of existing linear features seismic lines and cut lines as unofficial off-highway vehicle (OHV) trails. Seismic lines and cut lines are not designed for OHV use and can lead to the sediment-loading and disease transport into fish habitat.

Grizzly bears are classified as a threatened species in Alberta. Grizzlies in Alberta need secure habitat, free from excessive motorized access, including maintaining trail densities at or below 0.6 km/km2 in high quality grizzly bear habitat in Grizzly Bear Core Areas and at or below 1.2 km/km2 in all remaining grizzly bear range.

2018

In June, the provincial government announces their commitment to conduct a third party review of the science behind the angling closures to determine whether this is the appropriate course of action to recover native fish.

In April, the provincial government releases recommendations made by the North Saskatchewan Regional Plan Council in 2014. AWA provides a submission to the government, stating that the NSRAC recommendations fall short of the protection that is needed for the Bighorn Wildland and must include, at minimum, those areas promised for protection by the Alberta government since 1986.

In the Kiska/Wilson PLUZ and remaining public lands, AWA supports the establishment of Public Land Use Zones and undertaking sub regional planning initiatives to establish legislative limits on land uses including industrial activity and motorized recreation, while recognizing and protecting critical bull trout spawning areas and other key conservation values.

AWA also supports expanding protections of the North Saskatchewan, Ram, Brazeau, and Clearwater River corridors as it would help to provide water security and protect important wildlife migratory corridors. It is important to note that keeping riparian corridors ecologically healthy does not preclude recreation opportunities such as fishing, swimming, canoeing and low impact camping.

In March, whirling disease is discovered in the North Saskatchewan River watershed.

2017

The provincial government announces the North-Central Native Trout Recovery Program, a new initiative to recover threatened bull trout and other native fish species. The lower Ram River and sections of the North Saskatchewan River are selected as candidate sites for recovery work, which would include a host of actions such as habitat restoration and a 5 year angling closure. These closures are not implemented after concerns are raised from the public regarding the science behind the decision in addition to the concern that anglers are being restricted while other damaging activities to fish habitat are allowed to continue.

2016

A local fishing guide and a former director for Alberta fisheries call for an independent inquiry into the relationship between sediment and decreasing fish catch numbers downstream after the 2013 flood captured a number of gravel pits and flushed the sediment downstream.

2015

Following extensive industrial scale logging operations on Fall Creek, a major tributary to the Ram River, concerns are raised by the general public regarding extensive damage caused by clearcuts and the proliferation of OHV use following the construction of logging roads into the area.

2007

Eagle Point Provincial Park and Blue Rapids Provincial Recreation area are created.

2002

Alberta’s Agriculture and Food Department concludes that agricultural activity is a key factor in the appearance of two intestinal parasites, cryptosporidium and giardia, in Edmonton’s drinking water (“Tapped Out?” Westworld, April 2007).

1994

Alberta joins the Canadian Heritage Rivers System (CHRS), a federal-provincial program designed to recognize outstanding rivers of Canada. Alberta is the last province to join this program.

1989

The portion of the North Saskatchewan River within federal lands (Banff National Park) is designated as a Canadian Heritage River.

1982

AWA urges the Alberta government to participate in the proposed Canadian Heritage Rivers System (CHRS), a national conservation program designed to ensure sustainable management of the country’s leading rivers. AWA identifies a list of candidate rivers for protection under CHRS – including the North Saskatchewan River – and sits on various related committees throughout the process. On November 17, the Alberta Government announces that Alberta will not take part in Ottawa’s Canadian Heritage Rivers System.

1974

Construction of the Big Horn Dam near the confluence of the Bighorn and North Saskatchewan Rivers is completed for hydroelectricity, flooding valuable wildlife grazing lands and displacing First Nations from much of their traditional lands. The long reservoir is named Abraham Lake after Silas Abraham, patriarch of the Stoney Abraham family who lived on the Plains for more than 150 years and whose homes and gravesites are now flooded. Silas also worked as a wilderness guide for many of the first Europeans to the area (B. Milholland 2015).

1972

Construction of the Bighorn Dam on the North Saskatchewan River begins.

1961

White Goat and Siffleur Wilderness Areas are established.

1894

The Northwest Irrigation Act creates a “first-in-time, first-in-right” system of water allocation. Water rights are tied directly to land titles. Senior license holders receive their full entitlement before junior licensees receive their share. Licenses have few, if any, expiry terms. The water license remains valid as long as the specified use continues.

Under this Act, the CPR receives free water and very cheap land in exchange for building infrastructure and help with recruiting settlers. This leads to the CPR initiating irrigation projects in southern Alberta in the early 1900s.

1880s

The rapid disappearance of the bison forces most First Nations into government-surveyed reserves.

1885-1887

Canada’s first national park, Banff Hot Springs Reserve is established, which is expanded and renamed as Rocky Mountains Park two years later. The Stoney are removed and banned from entering the park.

1807

David Thompson establishes a trading post at Rocky Mountain House and travels to the Kootenay Plains and across Howse Pass to briefly establish a new trading area in British Columbia.

1795

The Hudson’s Bay Company builds its first fort in the vicinity of Edmonton; a number of different forts are built until the final version of Fort Edmonton is built in 1830 (B. Milholland 2015).

Late 1700s

The North West Company sends a number of men up the North Saskatchewan River in order to expand their fur trade, including David Thompson, John McDonald of Garth, and Duncan McGillivray (B. Milholland 2015). The Hudson’s Bay Company also established permanent posts.

Pre-Contact

The upper North Saskatchewan River corridor has been consistently used by Indigenous peoples since ice retreated about 10,000 years ago. Archeological evidence suggests that the earliest nomadic people in the area were the Upper Kootenay, part of the Ktunaxa Nation.

Over the past 500 and 200 years, respectively, the Assiniboine and Stoney Nakoda First Nations also moved into the region. More recently, as territorial boundaries were not definitive and fluctuated often, a number of other tribes also inhabited the region: the Peigan and the Blood, who joined to become part of the powerful Blackfoot Confederacy, were among these groups. The Sarcee people, now known as the Tsuu T’ina Nation near Calgary once occupied the upper North Saskatchewan River area and enjoyed a loose alliance with the Blackfoot.

There is also extensive archeological evidence of use along the North Saskatchewan River and watershed (Milholland 2015).