July 14, 2015

AWA Wilderness & Wildlife Defenders: Please Fill Out Bull Trout Survey

It is summer time and I’m sure everyone is out enjoying the beautiful Alberta outdoors;…

For the well-being of all living things, Alberta has healthy, natural ecosystems in its river headwaters.

There is plentiful clean water for all Albertans; province-wide awareness and stewardship of water as a precious, life-giving resource; and effective, ecosystem-based management of Alberta’s watersheds, groundwater, river valleys, lakes, and wetlands.

Water sustains life. It is critical for our food, sanitation, industry, recreation, and solace. Indeed, water has become a symbol of the health and vitality of both humans and ecosystems. In its many forms, it is also a significant symbol of Canada, pervading our visual art and literature.

Since AWA’s beginnings in the 1960s, we have focused on the health of Alberta’s watersheds, wild rivers, and wetlands, which we consider integral to the maintenance and well-being of all Albertans, including wildlife. We recognize that education, protection, and regulated management and use are the most democratic and efficient means of securing long-term water quality and of conserving aquatic ecosystems and their biological diversity.

Water relies on healthy ecosystems to remain clean, pure, and available. Protecting watersheds, wetlands, and wild, natural rivers is the cheapest and easiest way to provide clean, safe water, as well as many other benefits, including wildlife habitat, flood control, sanitation, and places for healthy forms of recreation.

Kinnaird Lake, Lakeland Provincial Park

With each passing year, water events like prolonged droughts and declining river flows, shrinking glaciers and increased flooding are increasing our awareness of the importance of water. Yet the multitude of threats that impact our water quality and quantity are increasing dramatically. Very few of Alberta’s watersheds remain intact. Our watersheds are being degraded at an alarming rate by activities such as forestry, mining, oil and gas development, cattle grazing, residential sprawl, and off-road vehicle use. But we, and our governments, are doing very little to conserve and protect this precious resource.

When conflicts arise, government decisions do not reflect what is needed to maintain healthy watersheds. Water quantity and quality, it seems, is not a high priority. If we are to protect and preserve our water heritage, this must change, and change quickly.

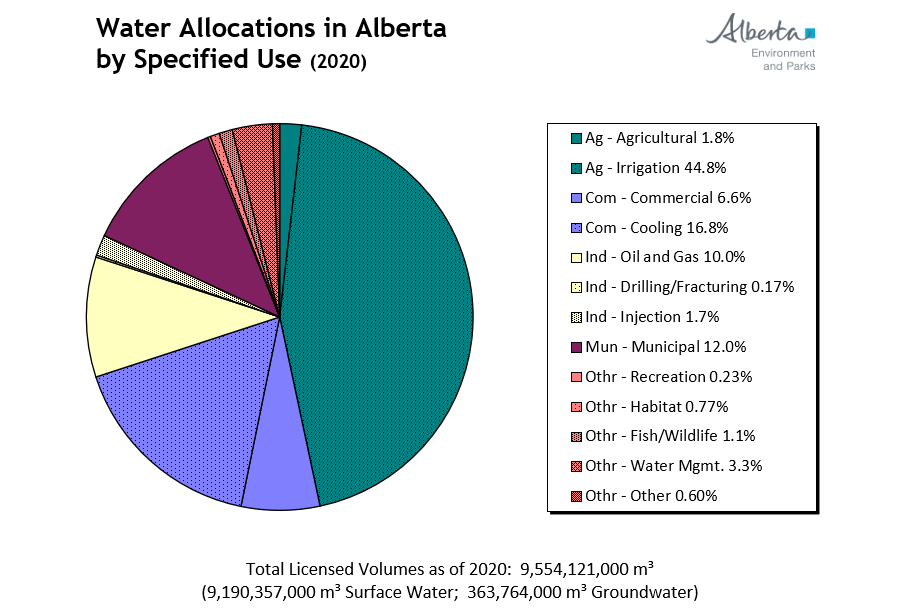

Figure 1: Water Allocations in Alberta by Specific Purpose (2020). c/o Alberta Environment and Protected Areas Water Policy Division.

According to the most recently available provincial data, Alberta has allocated over 9.5 billion cubic metres for use annually in the province (Figure 1). The agricultural sector, more specifically the 12 irrigation districts, hold the majority of water allocations (46.6%) in Alberta and have the oldest water licenses. This is meaningful, as under the province’s ‘First in Time, First in Right’ legislation, the most senior licenses are permitted to withdraw the entirety of their allocation first, regardless of purpose.

The proportion of water allocated is different from the volume of water actually used annually for each purpose. For example, in 2022, 1.6 billion cubic meters of water was used to irrigate in Alberta, consuming 17 % of the province’s total allocations. The volume allocated can be understood as the maximum amount of water available to use in a given year.

Water for commercial and cooling purposes (23.4%), municipalities (12.0%), and oil, gas, and other related industries (11.9%) make up the bulk of the remaining allocations (Figure 1). Altogether, water for the purposes of habitat, fish and wildlife, and water management receive just over 5% of all allocations.

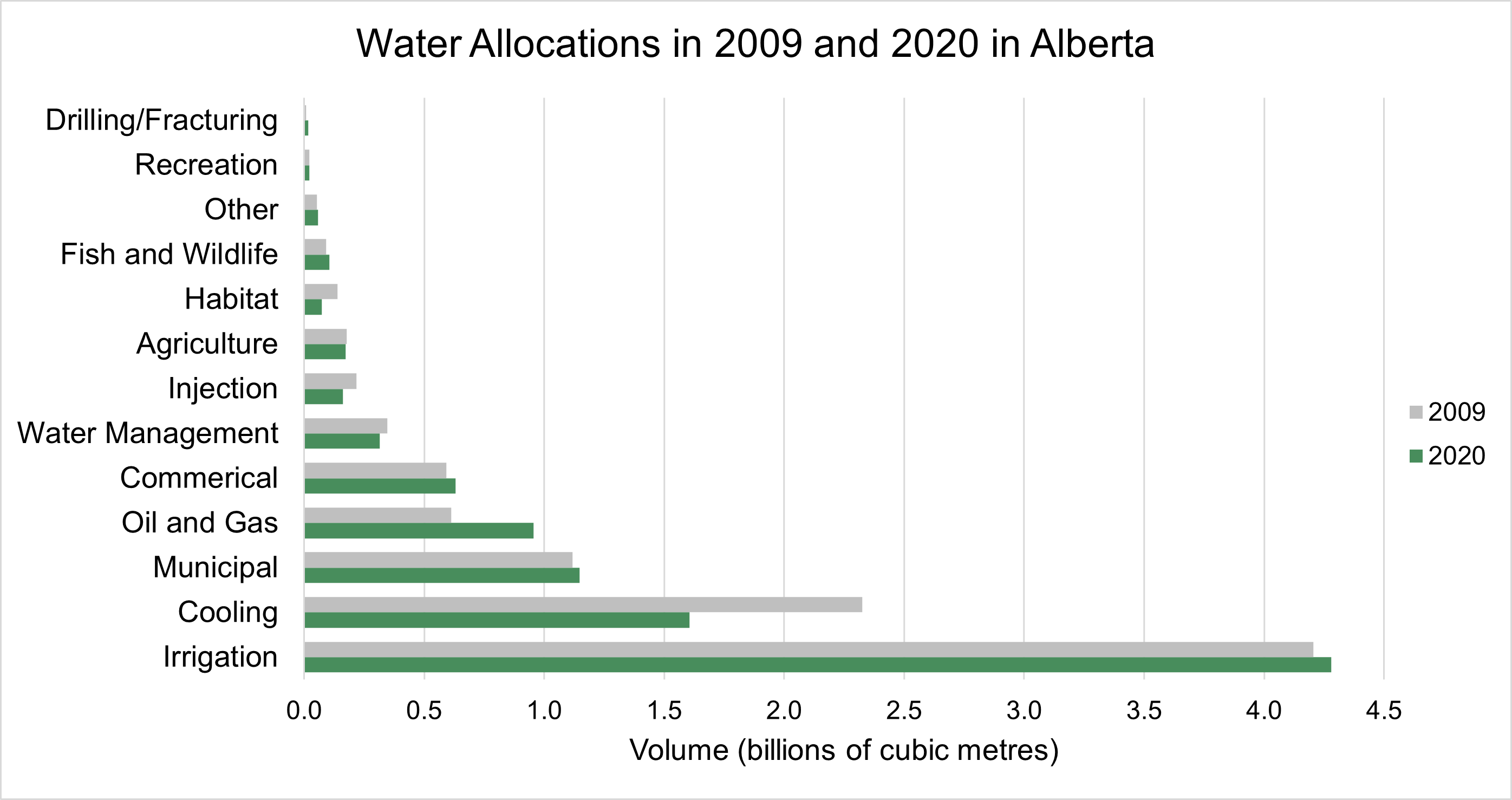

Figure 2: Water Allocations in 2009 and 2020 in Alberta. Based on data provided by Alberta Environment and Protected Areas Water Policy Division.

As of 2023 almost 4.3 billion cubic metres of water is allocated for irrigation (Figure 2). The next largest licensees are cooling with 1.6, municipalities with 1.1, and oil and gas with 0.9 billion cubic metres of allocations.

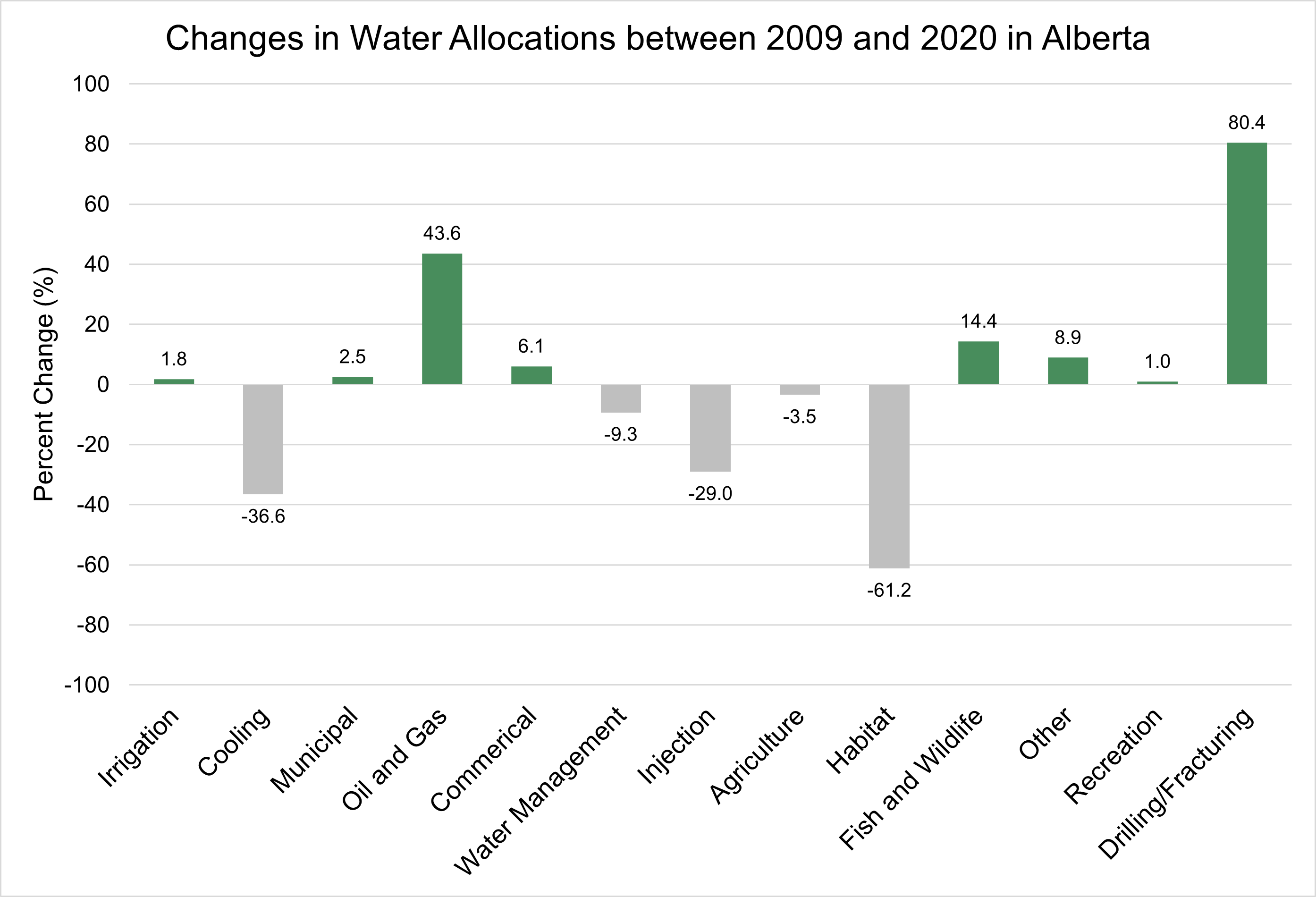

Figure 3: Changes in Water Allocations between 2009 and 2020 in Alberta. Based on data provided by Alberta Environment and Protected Areas Water Policy Division.

Since 2009, the overall volume of water allocated has decreased by 3.5%. This is owed largely to substantial reductions in water allocated for cooling purposes (Figure 2, Figure 3). The largest decrease however, is observed in water allocated for habitat purposes; since 2009, this volume has decreased by 61.2% (Figure 3).

Other sectors have had increases in their allocated volumes, including irrigation, municipalities, commercial, and fish and wildlife among others; the greatest increases are observed in water allocated for oil and gas (43.6%) and drilling/fracturing (80.4%).

There is an emerging realization of the importance of the water that flows through rivers and wetlands in sustaining healthy ecosystems. The final report of the 2003 conference on Canadian Wetland Stewardship placed the value of wetlands to Canadians at $20 billion annually. In 2004 Environment Canada estimated the value of freshwater to the Canadian economy to be between $7.5 and 23 billion annually – which puts the value of fresh water on par with the gross figures for agriculture and other major economic sectors. Although we need to value fresh water for more than its economic worth, putting a dollar value on nature’s services helps us to understand them within the context of our society’s usual way of measuring worth.

The Ecological Society of America describes ecological benefits or services as “the conditions and processes through which natural ecosystems, and the species that make them up, sustain and fulfill human life.” These benefits include water filtration and purification, waste disposal and detoxification, habitat for plants and animals, production of fish, flood control, recreation, tourism, and aesthetic appreciation.

Ecological services are expensive and even impossible to replace when aquatic ecosystems are degraded or lost. Today however, degradation and loss of these critical ecosystems are occurring at the greatest rate ever. Seventy percent of Alberta’s wetlands have been lost, mainly to agriculture.

Beaver pond, Lakeland Provincial Park

The health of aquatic ecosystems is largely dependent on issues of land use. The province of Alberta has been dragging its feet on developing a land-use strategy for over 15 years. Currently, the provincial government’s goal is to release a draft Land-use Framework in early 2008.

AWA has played a leading role in advocating for such a strategy, focused in particular on public lands management. In the fall of 2004, AWA convened a public land roundtable to begin developing a vision and fundamental guiding principles for our public lands. We followed this up with A Review of Public Land Policy in Alberta, British Columbia, the United States and New Zealand, completed in August 2005. During the summer and fall of 2007, we participated in the Land-Use Framework Working Group sessions, providing input for the Land-Use Framework promised by the government.

“Water is a sacred gift, an essential element that sustains and connects all life. It is not a commodity to be bought or sold. All people share an obligation to cooperate to ensure that water in all of its forms is protected and conserved with regard to the needs of all living things today and for future generations tomorrow.”

(Keepers of the Water Declaration, September 7, 2006)

“All the water that ever has been or ever will be is here now. It sits, it runs, it rises as mist. It evaporates and falls again as rain or snow. You cannot pollute a drop of water anywhere without eventually poisoning some distant place.” – (Michael Furtman, Writer)

Agriculture is the largest single sector using water in Alberta, with 46.6 % of all licensed water allocations in the province (as of 2020). Agriculture is also a highly consumptive water user, as water diverted from streams for crop production is not necessarily replaced by return flows. While there are some returns to the local hydrological cycle through plant evapotranspiration and groundwater recharge, as a surplus crop producer, much of Alberta’s yields are exported, which means that the water (and nutrients) within these crops also leave the province. This is known as virtual water trade. The majority of the agricultural water licenses are for irrigation purposes. In Alberta, 5.8 % of cultivated land in the province is irrigated. Paradoxically, the gains made over the decades by Alberta’s irrigation sector in terms of water-efficient irrigation technology decrease the quantity of return flows and increase the consumptive nature of the industry. Alberta Environment reported in 2002 that irrigation accounted for 71% of consumptive water use in Alberta.

The majority of irrigated hectares are concentrated within the 11 Irrigation Districts (IDs), which are located in the South Saskatchewan River Basin. This watershed has been closed to new water licenses and allocations since 2007, when it was recognized that its rivers and streams had been well overallocated and instream flow needs were regularly not being met. Despite this recognition, existing allocations have not been meaningfully reduced.

In 2022, the IDs diverted 2.5 billion cubic metres out of Alberta’s southern watersheds. Of this, over 1.8 billion cubic metres were used for irrigation. The irrigation infrastructure in the region is extensive; 8000 km of pipelines and canals transverse the landscape, connecting 56 reservoirs (with a total live storage capacity of 2.9 billion cubic meters) to the rivers and croplands. 236 million cubic metres, or 2.5 percent of Alberta’s total annual allocated volume, was lost through evaporation and seepage from ID infrastructure alone.

In 2022, Alberta’s largest crops by area were wheat, canola, tame hay, barley, and dry peas, of which a small proportion were located within the IDs (Graph 1). This is understandable, as these crop types are productive on dryland operations. Crops found predominately on ID lands included dry beans (96%), sugar beets (89%), potatoes (85%), and corn for grain (100%) and silage (51%), which are all crops that require greater volumes of water than average precipitation affords in southern Alberta. The input of additional water allows irrigators to grow more than 60 different varieties of crops on their lands, compared to the 29 types that grow on dryland farms.

The main benefit of irrigation is increased yields; of Alberta’s largest crops, comparisons of ID area and production percentages demonstrate IDs did produce more on less land, but still made up relatively small proportions of the total crop production, with the exception of corn silage (Graph 1). Looking at some of Alberta’s smaller crops, IDs contributed significantly to the province’s potato yields, producing 84 % of potatoes, or more than 1 million tonnes, as well as 87 % of sugar beets, equivalent to almost 880,000 tonnes (Graph 2). Assumedly, they would be responsible for the same percentage of total crop market receipts, and of the crops with market receipts reported, IDs had large proportions of potatoes and hemp sales, estimated to be $260 million and $60 million, respectively (Graph 1).

Otherwise, dryland operations produced the vast majority of Alberta’s crops and crop value, including over $7 billion worth of canola and wheat. This is the economy of scales; while irrigated cropland is technically more productive, Alberta has far more dryland operations that grow the majority of the province’s crops, and well in excess of what is needed to feed the province (while Alberta is a surplus producer of many crops and livestock there are some major deficiencies; the province only produces 5 % of the fruits and vegetables we consume). One strategy uses a massive amount of land (concentrated in the poorly protected and significantly degraded Grasslands Natural Region), while the other relies on enormous inputs of water. Neither of these are sustainable, but currently, the most pressing issue is that there is an extremely limited amount of water in Alberta, of which a massive amount is controlled by a small sector.

Alberta has only 2.2 percent of Canada’s freshwater supply but supports almost three quarters of the country’s irrigation. Growing irrigated crops, particularly in the semi-arid prairies, creates a huge displacement of water out of already water-scarce river basins. Consider the downstream impacts of these massive diversions – how much do water treatment facility costs increase without sufficient volumes to dilute pollutants? What about the costs of fish stocking programs, which release hatchery-reared species into the watersheds to reduce angling pressures on wild fish populations, who may otherwise be robust under natural flow conditions? Or the costs of erosion control and riparian habitat restoration? What does it cost when low river volumes force communities to reroute their intake pipes or truck in water over great distances? What about the value lost when weakened river systems cannot effectively cool the atmosphere, filter water, or support plants who produce oxygen, store carbon, and enrich the soil? These realities quickly complicate the cost-benefit analysis of irrigation.

Graph 1: Top Crops in Alberta. Data analysis and sources: All data is from the 2022 growing season A) ID cultivated hectares (Alberta Agriculture and Irrigation, 2023a) were calculated as a percentage of total seeded hectares in the province for each crop (Statistics Canada, 2023) B) ID cultivated hectares were multiplied by average crop insurance yields (Agriculture Financial Services Corporation, 2023) for irrigated crops to estimate ID production, and calculated as a percentage of total production (Alberta Agriculture and Irrigation, 2023b) C) Using the assumption that the ID’s proportion of production is equivalent to their proportion in crop market receipts, the ID’s crop values were estimated with reported total crop market receipts (Alberta Agriculture and Irrigation, 2023b) *Note: Where average crop insurance yields were not available, ID’s proportion of cultivated area relative to the total was used to estimate production and value data.

Graph 2: Other Crops in Alberta. Using the same datasets and methods described in graph 1, the area and production totals for other crops in Alberta were determined. Total crop market receipts were not available for the majority of these crops.

Several studies conducted in the 1990s indicated that agricultural practices were contributing to the degradation of surface water quality in Alberta and that the potential for impacts increases as agricultural intensity increases (Alberta Agriculture, Food and Rural Development, 2000). These studies also showed the following results:

Crop production has negative impacts on water in other ways as well. Food and biofuel production and waste production are all placing greater demands on the water supply and pressures on watersheds. Most of Alberta’s wetlands have been drained and filled, primarily for agriculture.

What can we do?

Intensive livestock operations are becoming a primary reason for groundwater overuse and a main source of water contamination. Cattle production has increased dramatically in recent years. There are 6 million cattle in Alberta, mostly in feedlots. Add to that 1.8 million pigs, again mainly in intensive situations. Animals require enormous amounts of water, both in direct consumption and in the forage crops grown on both dryland and irrigated farms. It is estimated that it takes 5,000 to 10,000 litres of water to produce 1 kilogram of beef. On average, that’s about 50 bathtubs full of water, or about 416 toilet flushes for a small beef roast.

Together, the cattle and hogs in our province produce the sewage equivalent of 87 million humans. A 1998 study under the Canada-Alberta Environmentally Sustainable Agriculture Agreement (CAESA) found that “agricultural practices are contributing to the degradation of water quality, [and that] the risk of …degradation by agriculture is highest in those areas of the province which use greater amounts of fertilizer and herbicides, and have greater livestock densities.” The study found that one-third of samples from 857 wells exceeded the Canadian Drinking Water Quality Guidelines for maximum acceptable concentrations of at least one parameter (Alberta Farmstead Water Quality Survey, Alberta Agriculture, Food and Rural Development, 1998).

Intensive agriculture may also be related to a trend of increasing fecal coliform presence in Alberta’s rivers. A 2001 Pembina Institute report states: “A parameter of great concern is fecal coliform bacteria. Bacterial content in water is indicated by the presence of coliform bacteria. Annual average monthly data recordings of fecal coliforms present in upstream locations have shown an increasing trend on the Athabasca, North Saskatchewan, Oldman and Red Deer Rivers since the 1970s” (The Alberta GPI Accounts: Water Resource and Quality).

In addition to causing contamination of water through wastes, cattle grazing in steep forested areas and aquatic ecosystems can also contribute to stream bank breakdown and siltation.

What can we do?

| Pollutant | Source | Impact on Water | Impact on Albertans |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sediment | Agriculture fields, pastures and livestock feedlots; logged hillsides; degraded streambanks; road construction | Reduced plant growth and diversity; reduced prey for predators; clogging of gills and filters; reduced survival of eggs and young; smothering of habitats | Increased water treatment costs; transport of toxics and nutrients; reduced availability of fish, shellfish and associated species; shortened lifespan of lakes, streams and artificial reservoirs and harbours |

| Nutrients | Cow pastures, hog barns and cattle feedlots; landscaped urban areas; raw and treated sewage discharges; industrial discharges | Algal blooms resulting in depressed oxygen levels and reduced diversity and growth of large plants; release of toxins from sediments; reduced diversity in vertebrate and invertebrate communities; fish kills | Increased water treatment costs; risk of reduced oxygen-carrying capacity in infant blood; possible generation of carcinogenic nitrosamines; reduced availability of fish, shellfish and associated species; impairment of recreational uses |

| Bacteria and parasites | Raw and partially treated sewage; animal manure. | Reduced survival and reproduction in fish. | Increased water treatment costs; increased intestinal disease |

Source: Adapted from the World Resources Institute by the Calgary Herald, January 21, 1998.

A huge benefit of our wilderness areas is the opportunities they provide for recreation, emotional well-being, and spiritual renewal. Hiking, camping, canoeing, and wildlife watching are all low-impact activities we can enjoy without damaging our watersheds. But some activities, such as off-highway vehicle (OHV) use and golfing can have detrimental impacts on watersheds.

When off-highway vehicle use is not confined to hardened trails with bridges, it can contribute unnecessarily to erosion, siltation, loss of fish habitat, and destruction of wetland ecosystems. On the May long weekend of 2007, the Indian Graves and McLean Creek areas bordering Kananaskis became a party site for more than 10,000 campers and off-highway vehicle users. They did so much damage to the area that the provincial government was finally compelled to establish a Forest Land Use Zone to limit further damage to the area.

Off-highway vehicle damage in the Ghost area (AWA files)

What can we do?

Golf courses consume large volumes of water and contribute to the chemical contamination of streams through the application of fertilizers, herbicides and fungicides. Golf course development also entails clearing vegetation, cutting forests, and creating artificial landscapes. These activities often have negative environmental effects, including land erosion, which can lead to siltation of rivers and streams; loss of natural wildlife habitat, including aquatic ecosystems; and blocking of the soil’s ability to retain water.

The watershed of the Upper Bow River alone, upstream of Calgary, contains more than 50 golf courses.

What can we do?

Currently there are two ways of extracting the underground bitumen in the oil sands areas. The more accessible bitumen near the surface is mined, which requires stripping away the boreal forest and scarring the land with deep open pits and toxic tailings water bodies. An estimated 81 percent of Alberta’s oil sands are too deep to be mined in this way. For these reserves, a process referred to as SAGD, Steam Assisted Gravity Drainage, is used to heat the viscous bitumen harboured deep in the ground so the oil can be pumped to the surface.

Pipelines for Petro-Canada’s MacKay River oil sands project (C. Campbell)

There is widespread recognition that this is the dirtiest oil in the world to extract, that we are literally scraping the bottom of the barrel. And the effects of oil sands development are felt far beyond Alberta’s borders. In a Globe and Mail article (October 26, 2007), Alberta oil sands projects are listed, along with other causes, as threatening Canada’s drinking water.

Tailings ponds such as this one next to the Athabasca River now cover approximately 50 km2 in the oil sands region north of Fort McMurray.

The changes that will be necessary to slow or halt further oil sands exploitation are made more challenging by the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). According to Maude Barlow, by currently using water from the Athabasca River to exploit the oil sands, American companies under NAFTA have established their “right” to that water.

“[I]f the Alberta government were to impose new regulations in the tar sands production in order to protect its water resources, the American energy companies would have to be grandfathered or paid substantial financial compensation” (Maude Barlow, Blue Covenant, 2007).

Oil Sands Reclamation

Reclamation of oil sands mines is not the panacea that it is often proclaimed to be. By the end of 2003, of the 33,000 ha of Alberta land disturbed for oil sands operations only 5,600 ha were under active reclamation. To date, after three decades of oil sands development, no reclamation certificates have been issued for land in the mineable oil sands area. Moreover, there is no known process to restore peat wetlands once destroyed. The habitat substitution of reclaimed grasslands in place of wetlands has unknown effects on the overall functioning of aquatic ecosystems, water quantity, and water quality in the boreal forest, and will almost certainly reduce biodiversity.

What can we do?

With demand for natural gas continuing to grow and conventional supplies on the decline, the oil and gas industry has turned its attention to coalbed methane (CBM) extraction.

CBM is found in the coal seams that underlie much of central and southern Alberta. Commercial production of CBM began in 2002. Coalbed methane wells tend to be shallow and lower-producing than conventional gas wells. Because of this, CBM typically involves a higher density of wells which in turn creates a greater level of disturbance on the land. The building of roads, pipelines, and well pads fragments and results in loss of wildlife habitat. These activities also negatively impact native vegetation.

A coalbed methane well in Rumsey Natural Area

Pembina Institute researchers Mary Griffiths and Chris Severson-Baker note that “the effect on the landscape will be greatest in wilderness areas and areas that do not already have an existing network of roads and pipelines. Yet, even in areas where oil and gas developments have already imprinted on the land, the additional effects of CBM operations may be dramatic due to the large number of well sites that may be needed” (Unconventional Gas: The Environmentaopmeta, June 2003)

It would indeed be prudent for the government to proceed with extreme caution in this relatively new area of resource extraction. CBM deposits are found throughout the populated Edmonton–Calgary corridor. Potential contamination of groundwater and/or surface water would have far-reaching impacts.

Alberta’s recent Royalty Review Panel recommended a lowering of royalties on low-producing wells. The Parkland Institute has criticized this recommendation, stating it will serve to stimulate increased coalbed methane development (Selling Albertans Short: Alberta’s Royalty Review Panel Fails the Public Interest, October 2007)

What can we do?

Willmore mountains (J. Hildebrand)

“To protect your rivers, protect your mountains.” (Emperor Yu of China, 1600 B.C.E)

Forests provide a broad range of valuable ecological services. They store water and purify it, maintain biodiversity, reduce air pollution and provide places for healthy recreation.

If a forest becomes unable to intercept, hold, filter, and slowly release pure water, its watershed is in trouble. In 2001 the UN warned that forests reduced by 40 percent can no longer provide full ecosystem services such as wildlife habitat, flood control and water purification. Some of Alberta’s forests have been reduced by 50 percent due mainly to logging and road building.

What can we do?

“The reality is that fresh water is more valuable than crude oil.” (Peter Lougheed, Former Alberta Premier, 2005)

Traditionally, water has been seen as being so abundant as to have no value. With the increasing realization that water is indeed limited in supply and more cannot be manufactured, its value is rising. This is leading to increased pressure to privatize water and turn it into a tradable commodity, like coffee or oil. Former Alberta Premier Peter Lougheed has cautioned against the commodification of water, saying, “With climate change and growing needs, Canadians will need all the fresh water we can conserve, particularly in the Western provinces” (Globe and Mail, Nov. 11, 2005).

The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) greatly hampers Canada’s ability to protect and conserve its water resources. NAFTA uses the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) definition of a tradable good, which includes water. Successive governments have denied that bulk water trade is included in NAFTA , but in 2001, when a business group in Newfoundland applied to export water from Gisborne Lake to the United States, then-Environment Minister David Anderson stated, “If Canada starts treating water as a commodity, or as an item of trade, it will ultimately be treated as an item of trade under NAFTA.” Under NAFTA rules then, if any province decides to export water, other provinces might be forced to follow suit.

Currently all provinces except New Brunswick have legislation in place banning the export of water and/or banning interbasin transfers. But in the absence of a strong federal policy, any province can change its legislation at any time and potentially affect the ability of all provinces to protect and conserve their water.

If proposals such as the Eastern Irrigation District’s recent request for an amendment to its water licence to allow it to lease or sell a portion of its water allocation were approved, this would be a step toward the commodification of water. AWA believes that water is a resource whose management and distribution should be kept in the public domain.

What can we do?

Global warming has emerged as the major issue of our day, threatening life on every corner of our planet. Industry is the major contributor to increasing greenhouse gas emissions. Alberta contributes about 30 percent of Canada’s total greenhouse gas emissions.

Most of Alberta’s emissions come from coal-fired electrical generating stations, oilsands exploitation, increasing intensive feedlot operations, and continuing conversion of forest and natural grasslands to cropland. Of these, oil sands exploitation will be by far the single fastest growing contributor in the near future. Leaks from natural gas pipelines continue to be a major source of greenhouse gases as well. In terms of personal consumption, emissions from transportation are up, in part due to increasing purchases of light trucks and SUVs – in 2005 emissions from this category were up a whopping 109 percent in Canada (Calgary Herald, October 1, 2007).

Banff – Jasper Parkway (J. Hildebrand)

The Eastern Slopes of the Rocky Mountains is the birthplace of four major river systems that carry water through all three prairie provinces and the Northwest Territories. Our current experience of global warming has seen colder weather arriving later in the fall, milder winters with more rain than snow, and earlier springs. Environment Canada’s Climate Change Impacts report notes that “glacier cover is now approaching the lowest experienced in the past 10,000 years.” Glaciers and the winter snowpack are nature’s reservoirs, storing water and releasing it through the hot summer months. With less total snowpack, and with glaciers fast disappearing (some predict the Bow Glacier will disappear within the next 30 years), water security for all life is threatened.

Rising temperatures also mean an increase in evapotranspiration, the process through which moisture is lost through both evaporation of surface waters and the breathing out of moisture by plants. We are already experiencing the results of this in more parched soils, the drying up of wetlands, and reduced flows in rivers and streams, all with significant impacts on humans, plants, and wildlife.

In the prairie provinces, global warming will likely be exacerbated by lengthy periods of drought that have been common in the region for centuries. The last 100 years have been somewhat of an anomaly in that scientists now believe they have been the wettest for at least a couple of millennia. According to water expert David Schindler, “Most earlier centuries had one or more prolonged droughts, some [lasting] 10-40 years.”

Many of the world’s most renowned scientists now fear that global warming may soon proceed with “speed and violence,” to use the words journalist Fred Pierce chose for the title for his 2007 book. At a meeting of the American Geophysical Union in December 2005, James Hansen of the NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies warned, “We are on the precipice of climate system tipping points beyond which there is no redemption.” The recently released Global Environment Outlook (October 2007), produced by authors from around the world for the UN Environment Program, reiterates the same concern: “Biophysical and social systems can reach tipping points, beyond which there are abrupt, accelerating, or potentially irreversible changes.”

One such tipping point was identified in Environment Canada’s report, Threats to Water Availability, cited by Chris Wood in his article “Melting Point” (Walrus, Oct. 2005):

“A climate-change time bomb will go off in the Arctic if peat, frozen for centuries beneath northern muskeg, begins to thaw and decompose – releasing billions of tonnes of greenhouse gases. ‘Canada’s peatlands are overwhelmingly important,’ notes Threats. They ‘contain twenty-five times the amount of fossil-fuel carbon released each year by the entire world.’ If released, the peat would initiate a feedback loop that could kick global warming into the catastrophic range.”

Our situation is not hopeless, however. The implementation of the Montreal Protocol of 1984 that suddenly and severely limited the production of ozone layer-destroying chlorofluorohydrocarbons (CFCs) shows that the world can take collective environmental action with immediate positive results.

What can we do?

According to demographic data released by Statistics Canada in September 2007, Alberta’s population is accelerating three times faster than the national average. It will reach an estimated nine million by 2050 if current growth rates continue.

Increased demand for water by an ever-growing human population will put huge demands on water supplies and healthy watersheds and aquatic ecosystems. Urban areas – with their higher density of vehicles and roads, construction, use of lawn chemicals, and improper waste disposal – can adversely impact watershed health. Pharmaceutical drugs, including hormones, are an increasing threat to water supplies because they are usually not filtered out by municipal sewage treatment. They negatively impact fish and possibly other animals and even humans. Some of these drugs can bioaccumulate, increasing their potency as they pass along the food chain.

“The economy is a wholly owned subsidiary of the environment, not the reverse.”

(Gaylord Anton Nelson, Earth Day Founder, 1916-2005)

What can we do?

In October 2007, Alberta Sustainable Resource Development released the Land-Use Framework Workbook Summary Report. The report compiles the views of the more than 3,000 Albertans who participated in government consultations over the summer of 2007. It acknowledges that Albertans want to see a slow-down in our rapidly growing economy. It also identifies public dissatisfaction with the “ad hoc approach” to land-use planning and concerns about inadequate environmental protection.

Not only is our population burgeoning in Alberta, but our levels of consumption are also skyrocketing. The “ecological footprint analysis” is a tool for determining if our lifestyles are sustainable. Ecological footprint is a measure of the load that human activities impose on nature. It calculates how much land is necessary to sustain current levels of resource consumption and waste discharge.

In Alberta, rather than changing our lifestyles to curb consumption and make progress toward sustainability, we increased our ecological footprint by 76 percent from 1961 to 2003. The ecological carrying capacity of the earth allows for just 1.8 ha/person. Alberta’s footprint now sits at 9 ha/person, making it the fourth largest in the world – 21 percent larger than the average Canadian footprint (Pembina Institute, August 2005).

The implications for water are great. Both energy and food, by far the two largest components of our ecological footprint, are particularly water intensive in Alberta. Heavily irrigated crops, intensive livestock operations, and water-intensive bitumen extraction in the oilsands all contribute to our oversized footprint. In addition to this, the emerging biofuel economy will undoubtedly also contribute to the growth of our footprint.

The bottom line is that our consumption, and the waste that accompanies it, places a huge burden on the earth’s water systems and is not sustainable.

What can we do?

Production and processing of biofuel is being promoted by both federal and provincial governments as a positive development that will boost rural economies and reduce greenhouse gases. But some biofuel production – particularly ethanol, which is made from crops like wheat, corn, and canola – involves high water use – is not compatible with Alberta’s semi-arid and drought-prone prairie landscape. In addition to the water necessary to grow crops, processing plants use from three to ten litres of water to produce one litre of ethanol. Ranchers have also raised concerns that biofuel production will raise the cost of feed as the energy sector competes with ranchers for crops.

Investing in biofuels will contribute to increased water stress in the prairies.

According to John Pomeroy and Michael Solohub of the Centre for Hydrology at the University of Saskatchewan, prairie agriculture has become more effective at using rainfall and snowmelt. Unfortunately, this efficiency has reduced the amount of surface water available to feed streams, fill small lakes, and recharge groundwater. Studying the prospects for biofuel, Pomeroy and Solohub concluded that using water for biofuel production and processing will “tend to use most or all available soil water in drier parts of Canada and reduce streamflow everywhere.” In turn, diminished streamflow will “reduce water availability for ecosystem services and human use and may degrade water quality in some cases” (November 2006, Biocap Canada Conference, Ottawa).

In their article published in the journal Science (August 2007), Renton Righelato of the World Land Trust and Dominick Spracklen of the University of Leeds conclude that “[i]f the prime object of policy on biofuels is mitigation of carbon dioxide-driven global warming, policy-makers may be better advised in the short term (30 years or so) to focus on increasing the efficiency of fossil fuel use, to conserve the existing forests and savannahs, and to restore natural forest and grassland habitats on cropland that is not needed for food.”

What can we do?

Scientists advise extreme caution in considering transfers of any quantity of fresh water from a river, lake, or aquifer. According to author Kevin Ma (The State of the Sturgeon River and the Alberta Water Crisis, 2006), water transfers between basins “almost guarantee the transfer of fish, plants and parasites between watersheds, creating fox-in-the-henhouse situations where newly introduced species run rampant due to lack of natural predators.” (R.V. Rasmussen – raysweb.net)

Alberta’s Water Act divides the province into seven large water basins. A special act of the legislature must be passed to allow for transfer of water between these basins. But each basin has many sub-basins, and transfers between sub-basins, known as intrabasin transfers, are permitted and occur frequently. For example, the Bow, Oldman, and Red Deer River watersheds are considered sub-basins of the South Saskatchewan River basin.

For decades, water has been withdrawn from the Bow River by the Western Irrigation District and Eastern Irrigation District, while return flows from these districts enter the Red Deer River.

Each sub-basin is distinct, and many have questioned the wisdom of allowing further transfers between them. This issue was recently brought to the forefront by a development near Balzac comprising a racetrack, casino, and mall. In April 2007 project construction was suspended since the developer had not secured a license for a water supply. With a moratorium on additional water allocations from the Bow and South Saskatchewan rivers, the developer looked to divert water from the Red Deer River for the project’s water supply. Since the proposed diversion was considered an intrabasin transfer, no special legislative action was needed to proceed with this transfer.

Public concern about this potential intrabasin transfer prompted Alberta Environment to create an Alberta Water Council Project Team to examine the implications of such transfers and to make suggestions for policy changes, if necessary – its report was still pending as of November 2007. In the end, the Balzac development secured water from the Bow River by buying a portion of a water license allocation from the Western Irrigation District.

Diversions of a river’s flow always carry ecological consequences and need to be considered carefully.

What can we do?

“What will happen in the tar sands when we must admit that the Athabasca River has given all she can to the steaming of bitumen? How many more casinos and race tracks will we contemplate in the Balzacs of Alberta when all the river basins are at maximum demand capacity in an era of declining flows?”

(Mike Robinson, President, Glenbow Museum, September 21, 2007)

Overallocation of a water resource results in insufficient instream flow to support healthy aquatic ecosystems. Water scientist David Schindler warns that waterways in southern Alberta are close to the point of no return. He says they still could be saved, but firm solutions are needed (Edson Leader, October 22, 2007).

In the northern part of the province the majority of water licences issued on the Athabasca River are for oil sands exploitation. “The oil sands are very close to oversubscribing the flow of the Athabasca,” Schindler says (William Marsden, Stupid to the Last Drop, 2007).

The roots of the current crisis of overallocation of the water supply in southern Alberta reach back to 1894 with the creation of Canada’s Northwest Irrigation Act. The intent of this act was to attract settlers to the prairies. Jeremy Schmidt, a PhD student at the University of Western Ontario, writes, “The government tied water licences directly to land claims and put few, if any, expiry terms on these agreements” (Alternatives 33:4, 2007). Water was allocated in a “first-in-time, first-in-right” basis. This created a hierarchy of licence holders, with senior licencees having the right to withdraw their full entitlement before junior licence holders receive their share of water.

With the 1930 Natural Resources Transfer Act, the provinces received authority to manage their own natural resources. In 1931, Alberta passed its own Water Resources Act and continued with the “first-in-time, first-in-right” system.

Water allocation proceeded with little understanding of the instream flows needed to maintain healthy aquatic ecosystems. When drought conditions led to water licences exceeding the available supply for the first time ever in 2001, the government began to look more seriously at ways to conserve water and increase water efficiency. In 2002 Alberta moved to a water market system that allows water licence holders to either transfer permanently or assign temporarily, for a price, the water rights formerly tied to their land. This move was intended to increase flexibility by, for example, allowing farmers who do not need their full allocations to transfer or assign a part of their water allocation to farmers who are experiencing shortages. A provision to hold back a maximum of 10 percent of the transfer amount was also incorporated into the water market. This measure is an attempt to address the issue of overallocation.

Questioning the ability of this provision to improve the viability of southern Alberta’s rivers, Jeremy Schmidt writes, “[W]ater is currently so overallocated that even if every licence changed hands twice – allowing for conservation holdbacks of up to 20 percent of allocated water – there would be only a moderate increase in flows left for the environment since, under the provisions of the system, recovered water would first go to junior licence-holders who do not receive their full allocations when there isn’t enough water to go around” (Alternatives 33:4, 2007).

In January 2007 the Government of Alberta established Water Conservation Objectives (WCOs) to be at least 45 percent of the natural rate of flow of the rivers within the South Saskatchewan River basin. However, with the exception of the Red Deer River, more than this amount has already been allocated in water licenses in this basin. As a result, in Alberta Environment’s words, WCOs are only “flow targets” that “provide direction on opportunities to increase flows in the highly allocated rivers in the Bow, Oldman and South Saskatchewan River Sub-basins.” (Source: http://www3.gov.ab.ca/env/water/regions/ssrb/WCO.html, retrieved November 19, 2007)

On August 21, 2007 the Eastern Irrigation District (EID) applied for an amendment to its water licences to broaden the purposes of those licenses from “irrigation and agriculture (stockwatering) purposes” to include many additional purposes, namely “municipal, agricultural, commercial, industrial, management of fish, management of wildlife habitat enhancement, and recreation” for their entire licensed water allocation.

The EID, the largest water licence holder in southern Alberta, received most of its water allocation in a1903 license, making it a very senior license holder. According to the Bow Riverkeeper organization, “On average, the EID only uses 76 percent of their allocated water. Some years, they use less than half of their allocation. There needs to be a debate over whether unused water should go back to the public domain. This proposal is a step in the opposite direction, encouraging the EID to maximize use of its existing license” (Bow Riverkeeper news release, Sept 5, 2007).

On October 23, 2007 the Government of Alberta decided to defer the EID request until it reviewed its policy on water license amendments in the South Saskatchewan River basin.

AWA believes that if Alberta Environment grants this request, or others like it, overall water management and allocation in the province will move out of public control into a private water market where environmental impacts are likely to be given low priority. Water management, including re-allocation of existing licenses, should be overseen by government, in the interest of the aquatic environment and of the general public, with opportunity for public input.

What can we do?

Roads, pipelines, and seismic lines can all be classified as “linear disturbances.” They crisscross our landscape with increasing density and have ecological consequences on wilderness, including forests, rivers and streams, and wildlife.

When such disturbances cross streams, they can increase bank erosion and stream sedimentation, alter drainage patterns, and destroy fish habitat. In addition to the damage that is initially caused, ongoing use of these pathways by off-highway vehicles and snowmobiles can continue and even increase the contamination of streams.

Forest ecologist Brad Stelfox has developed an award-winning landuse simulation tool. He has used it to track the alarming growth of human impact, including linear disturbances, on Alberta’s landscape and to predict future scenarios. Roads and seismic lines increase public access across the land, and managing access is a key issue in safeguarding our watersheds.

What can we do?

AWA continues to chair the Alberta Environmental Network’s Water Caucus, organizing its monthly calls and distributing the agenda and summary minutes for these meetings. Water Caucus members continued to exchange information on various water issues across the province including coal mining and oil sands impacts on water, AEP’s regulatory transformation, and the irrigation expansion project in the South Saskatchewan River Basin.

In August, AWA reached out to Alberta Transportation and the Special Areas Board to inquire about the current status of the Special Areas Water Supply Project. The Special Areas Board responded by saying that after reviewing the Engineering Confirmation study and the Environment Impact Assessment, the Special Areas Board moved not to advance further funding to the Special Areas Water Supply Project at this time.

In June, AWA submitted a letter to AEP detailing our comments on the Bow River Reservoir Options Phase 2 Feasibility Study. AEP is investigating three reservoir options for flood mitigation along the Bow River upstream from Calgary. Upon reviewing the available information, AWA does not support the creation of new on–stream dam infrastructure as a strategy for flood mitigation for Calgary and the surrounding communities. We feel that better alternative flood mitigation strategies exist – through improving upstream land uses and limiting future commercial, industrial, agricultural, and residential developments within the ecologically vital flood plain of the Bow River.

AWA submitted a comment letter addressing the draft Athabasca River Integrated Watershed Management Plan (IWMP), produced by the Athabasca Watershed Council (AWC) which was open for public feedback until June 30, 2021. AWA considers the IWMP to be an important strategic document that provides direction and a roadmap for future AWC–WPAC and partner activities. The recommendations we included would further strengthen this document through including more meaningful actions to protect the watershed for current and future generations.

In March, AWA, along with several other ENGOs including Southern Alberta Group for the Environment (SAGE), Trout Unlimited Canada, and Bow Valley Naturalists submitted a letter to government ministers at both the provincial and federal levels outlining our shared concerns regarding the recently approved project to expand irrigation infrastructure in the SSRB. This project proposes to upgrade open canals into pipelines, to build new and expanded storage reservoirs, and to increase irrigation acres within eight irrigation districts in the SSRB. We are asking that this monumental project be subject to the necessary environmental assessments, regulatory review, and opportunities for public and indigenous consultation and input.

In July, AWA submits our concerns to the Government of Alberta about a proposed gravel mining operation that we believe could harm aquatic ecosystems in a sensitive flood plain area between the Red Deer and Medicine Rivers.

In June, AWA writes a letter to the provincial government outlining the significant financial and environmental drawbacks of the Special Areas Water Pipeline proposal. An AWA representative was elected to the Board of the Red Deer River Watershed Alliance.

In May, AWA comments on draft Canadian water quality guidelines for neonicotinoid insecticides; we were

concerned the draft thresholds were too low for exposure events, and did not consider environmental conditions and interactions with fertilizers and other chemicals that can intensify the pesticides’ impacts.

In March, for the Peace watershed, AWA comments on the Wapiti River water management plan. We generally supported its overall objectives, and how its proposed Water Conservation Objectives were chosen to maintain a certain level of ecological integrity while addressing social and economic demands.

In January, AWA commented on draft Canadian groundwater quality guidelines, seeking stronger linkages between cumulative land–use issues and groundwater quality.

In November, AWA became the ENGO representative for the new wetland technical advisory committee (TAC) within the federal–provincial Oil Sands Monitoring program.

In October, AWA submits comments to the Government of Alberta on Bow River flood mitigation concepts. AWA believes that the primary strategy for flood mitigation for Calgary and surrounding communities should not be on–stream dam infrastructure, but rather upstream land use improvements, and strictly limiting the future establishment of commercial, industrial and residential developments within the floodplain of the Bow River.

In September, a guest–authored article outlining how wetland policy is applied in Alberta’s settled areas, describing progress and gaps remaining in wetland policy implementation there, is presented in the Wild Lands Advocate.

In September, Alberta’s Wetland Policy is finally released. The policy finally abandons the concept of no-net loss of wetlands, and exempts all approved and near-term foreseeable oilsands projects from wetland offsets or restoration. Environmental groups believe the policy is not sufficient to protect wetlands of significant biodiversity and ecosystem function. The policy contains no overarching goal to maintain wetland area (contrary to the non-consensus recommendations of the Alberta Water Council) let alone to maintain or restore wetland function. Avoidance of damage to existing wetlands is given only lip service, in favour of minimizing disturbance impact and mitigation. If a company decides that avoidance is “not practicable” they must “adequately demonstrate that alternative projects, project designs, and /or project sites have been thoroughly considered and ruled out for justifiable reasons.” Any compensation payments for wetland loss will not necessarily be spent on wetland replacement: instead they may be spent on education or outreach.

In August, the Alberta government releases a report that it received in December 2012 recommending safety improvements in Alberta’s pipeline system. Key findings include a need for better management of water body crossings, stronger inspection and testing requirements in high risk areas, and stronger audit and enforcement capacity by the energy regulator.

In June, floods cause extensive damage across southern Alberta. Trails throughout areas such as Kananaskis Country, the Ghost and the Bighorn suffer enormous damage.

In March, a burst waste water line at a Suncor Energy tar sands strip mining operation causes 350,000 litres of contaminated water to overflow in to the Athabasca River. This is the second toxic water spill to occur from Pond C in the past two years.

Alberta’s Westslope Cutthroat Trout is finally designated as a threatened species, seven years after COSEWIC submitted the recommendation to the federal government. The species was once widespread throughout southern Alberta but is now found only the the Bow and Oldman drainages.

In December, ignoring calls from its own Fish and Wildlife Scientists, Alberta Environment and Sustainable Resource Development allows logging in Hidden Creek, the most important spawning grounds for threatened bull trout in the entire Oldman River system in southern Alberta, and also home to threatened westslope cutthroat trout.

In June, a pipeline leak north of Sundre spills between 1,000 and 3,000 barrels (160,000-475,000 litres) of light sour crude oil into the Red Deer River, a major drinking water source for southern Alberta, via Jackson Creek, which contains threatened bull trout. This news comes only weeks after a pipeline leak in northern Alberta spills approximately 5,000 barrels (800,000 litres) of oil into surrounding peat wetlands.

In April, a new research paper by a University of Alberta ecologist, Dr. Lee Foote, concludes that the government should negotiate mineable oil sands development limits. The paper cites doubtful reclamation success for the extensive peat wetlands central to that landscape. Dr. Foote’s paper states that:

In March, University of Alberta scientists Rooney, Bayley and Schindler release a study emphasizing that peatlands cannot be reclaimed once destroyed by tar sands mines. As they cover 65% of the pre-mining landscape, this loss will have far-reaching impacts on regional ecology and biodiversity that have not been assessed. This loss also represents a large unaccounted-for source of carbon emissions.

In July, Special Areas water Supply project rears its ugly head once again. The Special Areas Water Supply Project would remove an undetermined volume of water from the Red Deer River to be used principally for irrigation agriculture, as well as some municipal improvement and undefined “environmental” uses. The proposal would see Albertans foot the enormous bill for a low value, environmentally-damaging engineering project.

The Project has been on the government books, in one form or another, for twenty years. The previous version of the proposals, which AWA fought strongly against in 2005, would have seen a $200 million bill paid by the Alberta taxpayer (or $60 paid by every single Albertan!). For its minimal economic benefit (a government economic study found that the project would return only 70 cents per dollar spent), the project had potential to do significant damage to the Red Deer river ecosystem and to areas of native grasslands which stood to be ploughed up and used for irrigation agriculture.

Although the Alberta government announces that it will be carrying out a three-year environmental assessment of the project, no details are released concerning how the project compares to previous versions: what the cost will be, or how much water will be removed.

In March, toxic water is released from water from Suncor Energy’s Pond C into the Athabasca River.

In July, the Alberta Utilities Commission (AUC) launches an inquiry to examine opportunities to “streamline” regulatory processes for hydroelectric power generation projects. AWA commissions and submits to the AUC two original reports to inform its own participation in this inquiry. One study details the impacts of hydroelectric projects – from large dam reservoirs to micro-hydro run-of-river projects – on riverine ecosystems, the other study examines impacts to river corridors and uplands from hydroelectric projects that could further jeopardize Alberta’s meeting its biodiversity commitments. In the coming year AWA will participate in inquiry workshops and submit final comments on the importance of an overarching protected areas strategy plus rigorous environmental assessment and cumulative effects management of hydroelectric developments.

In spring, AWA helps publicize a leaked provincial wetland policy draft that indeed removes the “no net loss” policy goal and drastically downgrades boreal peatlands because of unproven assertions that abundant wetlands have less value. AWA continues to advocate for a provincial wetland policy that values the critical importance of both boreal and prairie wetlands on the landscape and works to protect them from further loss at a provincial scale. Progress on this policy had stalled since autumn 2008, after the three year process of the Water Council Wetland Policy Project Team yielded a compromise policy supported by 23 of 25 sectors, with non-consensus letters from the tar sands mining and petroleum sectors.

In spring 2010, AWA is instrumental in bringing to light a public web site posting by the Alberta Chamber of Resources, a tar sands industry association, that the provincial government had in early 2009 agreed to their key demands to undermine the “no net loss” policy.

In March, AWA presents our research on groundwater risks from in situ tar sands development to First Nations and other community members in Anzac, the town of Athabasca, Lac La Biche and Cold Lake. AWA joins with other groups in opposing the precedent-setting application by Nexen Inc. to sharply revise its Long Lake in situ water plan towards reliance on the Clearwater River water for its freshwater requirements instead of local groundwater sources as it had pledged to do. AWA also participated on the multi-stakeholder federal-provincial committee recommending long-term withdrawal rules and monitoring of Athabasca River water withdrawals by tar sands mines, which completed its work in early 2010. With other ENGO partners, AWA strongly advocates for an absolute cutoff of withdrawals during low winter flows. To aid in transparency and decision making, AWA develops a model to present compliance costs of various rules in the context of other capital costs incurred by tar sands companies. The overall work of this committee is presented to community members in the town of Athabasca in March 2010. AWA also presents at a climate change adaptation conference in Austin, Texas on the innovative modeling of climate change-affected river flows by this Athabasca committee.

In May, following up on the November 2008 science workshop, an implementers workshop discusses best practice management of parks, forests, rangeland and municipalities in the headwaters. One affirmation of this work is the selection by the Bow River Basin Council of land use focused on wetland, riparian and headwaters regions for its Phase 2 watershed management planning. AWA advocates for source water protection as the Eastern Slopes priority land use within the South Saskatchewan region’s land use planning.

In November, collaborating with several government and non-government organizations, AWA takes a lead role organizing two workshops to build awareness and support for excellent headwaters management. Decision makers and policy influencers from the North and South Saskatchewan watersheds attend the November 2008 science workshop, featuring top researchers discussing the effects of headwaters snow pack, multiple land uses and climate change on downstream water quality and quantity.

In November, AWA’s water economist and conservation specialist Carolyn Campbell attends the first Alberta Water Council meeting that includes the new members (including AWA), who were appointed in December 2006. The new members did not gain full membership until the transition to non-profit status was complete.

A coalition of citizen-based organizations, including AWA, submits a report to the Alberta Water Council called Recommendations for Renewal of Water for Life: Alberta’s Strategy for Sustainability. The issues addressed include the need for source water protection, insufficient progress on protecting healthy aquatic ecosystems, integration of land use and water use in watershed planning, improving conservation by moving from supply-side to demand-side management, and watershed governance.

On October 26, the Alberta government defers its review of the Eastern Irrigation District’s application to amend its water licenses while examining the current policy on water license amendments related to the South Saskatchewan River Basin.

“With most of the South Saskatchewan River Basin closed to new license applications, concerns have been raised about the Alberta government maintaining its authority to oversee water resources. We need to ensure water is allocated in a fair manner with opportunity for all users to have access to water resources” (Environment Minister Rob Renner, Government of Alberta News Release).

On October 3, the Alberta Water Research Institute issues its first call for proposals to “tackle some of Alberta’s most pressing water-related environmental issues, including habitat decline, biodiversity loss, water flow and water quality” (AWRI and Alberta Ingenuity Fund News Release).

On September 28, Alberta Environment approves a water transfer from the Western Irrigation District (WID) to the MD of Rockyview for a controversial development near Balzac that includes a racetrack, mall, casino, and veterinary college. Concerns have been raised that this development does not constitute a wise use of water in a water-scarce region. This transfer will be the largest and most expensive ($15 million) water allocation transfer in the province since the inception of the water allocation trading system in 2002.

The government applies the maximum 10 percent holdback (under the Water Act) to this transfer: 10 percent of the water transfer is held back to contribute to streamflow in the Bow River. This is a small success for the environment.

On September 27, the Horseshoe Lands Area Structure Plan unanimously passes its third reading in the MD of Bighorn Council. This plan includes a new townsite that will accommodate up to 5,600 people in 2,900 residences, as well as commercial and industrial facilities, on the banks of the Bow River near Seebe.

The environmental community opposes this plan because it has no guaranteed source of water for its full implementation. In addition, no environmental impact assessment has been undertaken to assess the cumulative impacts of the proposed development, including impacts on the aquatic environment and the water resources in the region.

From September to October, AWA participates in public consultations initiated by the Wetland Policy Project Team of the Alberta Water Council about a new Wetland Policy and Implementation Plan. The information gathered will guide the drafting of the new policy, which the Team plans to deliver to the government by early 2008.

On August 21, the Eastern Irrigation District (EID) applies for an amendment to its water license to allow it to lease or sell a portion of its water allocation. The EID is the largest water license holder in southern Alberta. It received its allocation in 1903 and uses only an average of 76 percent of its allocated water. “There needs to be a debate over whether unused water should go back to the public domain. This proposal is a step in the opposite direction, encouraging the EID to maximize use of its existing license” (Bow Riverkeeper News Release, September 5, 2007).

Of deepest concern is that granting this request will take water out of public control. It will allow the EID to profit from water that it receives for free in a private water market. “The purposes for the water and its allocation should be subject to the constraints of Alberta’s Water Act and dealt with through basin plans and the market mechanisms for license transfers that are available in the Water Act…. This would be another poor decision if it were to be approved, allowing water allocation decisions without public input or government direction” (Wild Lands Advocate, October 2007).

On August 2, 328 farmers of the Western Irrigation District vote 57 percent in favour of transferring some of their Bow River water rights to the mega-mall, casino, horse track, and veterinary college development near Balzac. This $1 billion development just north of Calgary is the largest project in Alberta outside of the oil sands.

In July, AWA releases a position paper on forestry, The Forests of Alberta’s Southern Eastern Slopes: Forests or Forestry?, calling for a full independent comprehensive review of forestry in southern Alberta: “Alberta Wilderness Association (AWA) is committed to maintaining healthy and intact forest ecosystems that will sustain biological diversity and viable wildlife populations, provide clean drinking water and promote long-term economic opportunities…. Water quality and quantity are recognized as key products of all forests and a primary product of the Eastern Slopes watersheds.”

In June, the Southern Alberta Land Trust Society releases The Changing Landscape of the Southern Alberta Foothills. This is the final product of the Southern Foothills Study (SFS), led by Dr. Brad Stelfox.

“SFS is a broad alliance of municipalities, landowners, industry, and environmentalists, including AWA, formed in 2005 to study current and future land-use trends and to provide a base upon which local landowners and government can plan for the future. The study area comprises 1.22 million hectares of fescue grassland, foothills, forest, and mountains” (Wild Lands Advocate, February 2007).

The study used the ALCES (Alberta Landscape Cumulative Effects Simulator) model to conclude that 50 years from now, “business as usual” will lead to a slow but steady environmental degradation of the south Eastern Slopes of the Rocky Mountains, including the following: doubling of the human population, 56 percent increase in number of cattle, increase of cutblock edge from 2,500 to 6,500 km, annual increase of 300 to 500 km of seismic lines, and 25 times increase in number of wells.

The results of the study were presented to 600 members of the public through a series of seven public meetings. Feedback from both the written survey (distributed at meetings) and a random sample telephone survey of an additional 800 people indicates that water quality and quantity is an area of very high concern. The written survey results showed that “reduced water quality” was the issue of greatest concern, with 84.8 percent of respondents saying they were “very concerned”; only 24.3 percent were “very concerned” about the loss of recreational areas. The written and telephone surveys also indicate that watershed protection was the “primary concern” of respondents. Over 70 percent of all respondents were “very concerned” about the diminished water quality and quantity predicted by the “business as usual” scenario.”

As part of a letter-writing campaign to establish Andy Russell-I’tai sah kòp Park in the Castle Wilderness, Sierra Club notes, “Although comparatively small in land area, the proposed park is the single largest source of flowing water for the Prairie Provinces and the importance of its protection was noted in the recent Rosenberg International Forum on Water Policy.”

In May, since the launch of the Water for Life strategy in 2003, 14 percent of Alberta’s land base (23 percent of the province’s public land) has been leased for petroleum and natural gas production. More than 18 percent of those leases were sold for oil sand exploration, which is – along with agriculture – one of the thirstiest of our industries.

In April, a coalition of 12 conservation and landowner groups, including AWA, sign on to a letter to Premier Ed Stelmach requesting a temporary moratorium on development in the Eastern Slopes watersheds. The coalition requests an initial response within two weeks and also requests meetings with the ministers of Environment, Sustainable Resource Development, Energy, and Municipal Affairs.

On June 8, 2007, the Premier turns down the request. John Cross, owner of the A7 Ranche at Nanton and a signatory on the coalition’s letter, describes the Premier’s response as “business as usual” until the new Land Use Framework guidelines are completed, meaning a continued increase in environmental degradation. A draft of the Land Use Framework is expected by early 2008.

Dr. David Schindler, a Killam Memorial Professor of Ecology at the University of Alberta and world-renowned water expert, is named chair of the Water Institute’s international research advisory council.

The Pembina Institute report Protecting Water, Producing Gas is released. This report highlights a number of groundwater issues that need addressing in the province:

In March, the Rosenberg International Forum on Water Policy releases its report Lessons for Canada and Alberta. The report highlights the importance of undertaking headwater protection. The authors conclude, “Upland watershed protection will become more and more important as population growth, diminishment of water supply and climate change conspire to change the hydrology of the Canadian West.” In particular, the headwaters of the Oldman River Basin “may be a good candidate for special watershed protection.” The report highlights the proposed Andy Russell–I’tai sah kòp Park in particular, stating that its protection “will pay for itself over and over again in the value of ecological services it provides alone” (Rosenberg International Forum on Water Policy, Program Synopsis and Lessons for Canada and Alberta, Forum V Report, pp. 90-91).

The Beaver River Watershed Alliance becomes the official Watershed Planning and Advisory Council (WPAC) for the Cold Lake/Beaver River area.

Environment Minister Rob Renner initiates a renewal of the Water for Life strategy. The review is undertaken by the Alberta Water Council and includes a public consultation process.

In February, Report of the Rosenberg International Forum on Water Policy to the Ministry of Environment, Province of Alberta is published. The Rosenberg Report, as it becomes known, is an analysis of the Water for Life strategy and was commissioned by the Alberta government in September 2006. The report emphasizes the importance of acknowledging the link between surface and groundwater, stressing that “the plan does not account sufficiently for groundwater or the relationships between water-air-land.” Among its many recommendations are the following:

Water Management Framework for the Lower Athabasca is released. The claim is that it “is designed to protect the ecological integrity of the lower Athabasca River during oil sands development.” In a joint news release, Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation, Fort Chipewyan Elders, Mikisew Cree First Nation, and Pembina Institute take issue with that declaration, stating that the government is “misleading Albertans and Canadians because it does not require industry to turn off its pumps when the river hits the red zone.” The framework defines three status levels – green, amber, and red – depending on in-stream flows. The red status is defined as “a zone where withdrawal impacts are potentially significant and long-term, depending on duration and frequency of withdrawals” – in other words, where withdrawals threaten the river’s ecological integrity. Although the Framework caps the amount that can be withdrawn in the red zone, it does not put in place a threshold where withdrawals have to stop to protect the river.

In January, the Lesser Slave Watershed Council becomes the official Watershed Planning and Advisory Council (WPAC) for the Lesser Slave Lake / Lesser Slave River watershed.

In December, the Battle River Watershed Alliance is officially designated as the Watershed Planning and Advisory Council (WPAC) for the Battle River Basin.

AWA is appointed to fill one of three additional ENGO positions on the Alberta Water Council. This body operates under the direction of Alberta Environment and was mandated in 2004 to “monitor and steward implementation of the Water for Life strategy,” launched in 2003. The new members will not gain full membership, however, until the transition from a government body to an arm’s-length non-profit organization is complete.

In November, the Government of Alberta invests $30 million to establish the Alberta Water Research Institute through Alberta Ingenuity. The Institute is to implement a water research strategy focused on safe drinking water, efficient water use, and healthy watersheds.

Eau Canada: The Future of Canada’s Water is published by UBC Press. This anthology compiles the opinions of water experts across the nation with regard to governance of the water in Canada and how it can be improved.

In the introduction, Karen Bakker, director of the Program on Water Governance at UBC, describes water governance in Canada as being in a state of crisis. She identifies the underpinnings of this crisis as “a mistaken belief in water’s unlimited abundance; an assumption that water resources can be diverted to suit human purposes, with little regard for environmental monitoring, and a lack of data and enforcement.” She describes current water legislation as “a patchwork of provincial and federal laws, with inconsistencies and gaps in important areas of responsibility and oversight.”

In their contribution to the book, lawyers Paul Muldoon and Theresa McClenaghan argue that provincial-federal turf wars are at the core of the current stalemate in water policy at the national level. They advocate for “a new governance framework that enables provincial and federal levels of government to work together to streamline and enforce existing legislation.”

In September, Alberta Environment hosts the Rosenberg International Forum on Water Policy in Banff. Alberta Environment asks the forum to assemble an international panel to review the province’s four-year-old Water for Life strategy and Alberta’s groundwater management.

In August, the Alberta government announces the South Saskatchewan Water Management Plan. Citing overallocation, a moratorium on new applications for water licenses for the Bow, Oldman and South Saskatchewan river sub-basins is put in place. AWA supports the closure of these rivers to future water allocations.

Water expert Dr. David Schindler offers these comments on the new plan: “I still don’t think we’re moving fast enough. I see some good first steps … but it’s like watching someone walking and an express train, which is the rate of development in this province” (Calgary Herald, September 13, 2006).

AWA produces the brochure Upper Oldman Headwaters: The Source of Our Water. It describes the headwaters area and provides information on old-growth forests, watersheds, and wildlife. It also challenges current Alberta forestry practices and calls for an end to industrial forestry south of the Trans-Canada Highway.

On June 16, AWA participates in the Planning Committee for the workshop Groundwater Sustainability in Southern Alberta: The Invisible Resource presented by the Bow River Basin Council. The workshop states the following objectives:

Thirteen priority actions are identified.

In May, the provincial government makes baseline testing of water wells mandatory prior to coalbed methane drilling.

A federal review panel is formed by the Ministry of Indian Affairs and Northern Development to investigate the situation on Alberta’s First Nations reserves. “Contaminated drinking water on Alberta reserves is to blame for sickness and possible even deaths. A water supply official for the Saddle Lake First Nation, one of Canada’s largest reserves with more than 7,000 residents, gave a grim outline of foul water and sick residents during his presentation to the expert panel. ‘We’ve got death at the tap,’ said Tony Stienhaurer, who says the reserve has also been under a boil water order since 2004. ‘We’ve got a high incidence rate of cancers, diabetes and young children that are born with cancer’” (Globe and Mail, June 7, 2006). “Nearly 60 percent of reserve drinking water systems in Alberta remain ‘at risk,’ and of the province’s 78 First Nations water operators, only 14 are fully certified” (CBC News, February 23, 2006).

In April, water experts David Schindler and Bill Donahue predict that “in the near future climate warming, via its effects on glaciers, snowpacks, and evaporation, will combine with cyclic drought and rapidly increasing human activity in the western prairie provinces to cause a crisis in water quantity and quality with far-reaching implications” (“An Impending Water Crisis in Canada’s Western Prairie Provinces,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America).

In February, the Milk River Watershed Council Canada is officially designated as the Watershed Planning and Advisory Council (WPAC) for the Milk River Basin.

In January, the Government of Alberta publishes Standards and Guidelines for Municipal Waterworks, Wastewater and Storm Drainage Systems. This document sets out the regulated minimum standards and requirements for municipal waterworks in Alberta. Alberta Environment is responsible for the Drinking Water and Wastewater Programs for large public systems in Alberta.

The Alberta Water Council begins a long transition to become an arm’s-length organization of the government; the first meeting that includes the new Council members (chosen in December 2006) is held in November 2007.