Forestry in Alberta: Then and Now

August 16, 2024

- •

- •

- •

The arrival of European settlers ushered in a stark shift in the care for forests, viewing trees merely as fuel, lumber, or even pests.

Logging fragments our forests and leaves behind unsightly roads, as seen in Star Creek. Photo © B. Verbeek.

By Devon Earl

Read the PDF version here.

When folks hear about the logging plans slated for Alberta’s Eastern Slopes in the coming years, they often raise an eyebrow. “How is that even allowed? Aren’t there any rules for logging?” they ask me. It’s a fair question, especially considering that logging companies are eyeing up forests near popular trails and critical habitat for at-risk species. Unfortunately, these occurrences are not anomalies but rather the norm. To understand why forestry seems to operate without regard for the public or the environment, let’s take a look back at the history of the industry in Alberta.

When delving into the history of forestry, we can’t overlook the Indigenous communities who cared for Alberta’s wilderness long before colonial interests took hold. For millennia, Alberta’s expansive forests were not just resources, but lifelines — providing food, medicine, wisdom, and opportunities for spiritual connection. As you may already know, Indigenous peoples have a rich tradition of using controlled fires to manage forests and nurture wildlife habitats. However, the arrival of European settlers ushered in a stark shift in perspective, viewing trees merely as fuel, lumber, or even pests.

The beginnings of forestry in Alberta

In the early 1800s, timber was primarily reserved for Britain’s Royal Navy, but modifications in 1826 allowed for the public sale of lumber deemed unsuitable for shipbuilding. In 1846, new legislation set the framework for the model of forestry that still prevails today, where harvesting rights are leased out to companies while the lands remain public. Settlers in Alberta built the first commercial sawmills around 1880, and the construction of railways in the following years bolstered Alberta’s nascent forestry industry. When the railway came to Calgary in 1883, there was a high demand for timber from the Eastern Slopes to be used as building materials. Timber was floated down rivers to be processed by sawmills in Calgary and Lethbridge. However, the arrival of railways also ignited many forest fires, prompting concerns about timber preservation and forest conservation.

The concept of forest reserves emerged in part from these concerns, including the establishment of the Rocky Mountain Forest Reserve, which aimed to preserve timber and protect water by preserving forests in the upper headwaters of the Eastern Slopes. Established in 1910, the Rocky Mountain Forest Reserve recognized that these landscapes supplied water to the river systems upon which settlement and development relied, highlighting the need for thoughtful and responsible management. Since then, protected areas and other forms of land -use management have been established in these areas, with differing levels of protection, industrial development, and acknowledgement of the importance of headwaters forests.

Shortly after Canadian provinces gained control over natural resources in 1930, the Alberta Forest Service was established. The Alberta Forests Act was written in 1949, and still governs forestry today, though with amendments. The key feature of the Forests Act is that it required forestry to operate under a “sustained yield” model. Although the wording has since been modified slightly, the Forests Act gave rights to the responsible minister to enter into a forest management agreement (FMA) “to enable that person to enter on forest land for the purpose of establishing, growing and harvesting timber in a manner designed to provide a perpetual sustained yield.” In a nutshell, this meant that the rate of forest harvest should be sustainable in the sense that timber harvesting should be able to continue at the same rate in perpetuity. This required reforestation of harvested areas, but it did not require forest harvesting to be sustainable in the sense that the forests would continue to provide ecological services (such as watershed integrity, carbon storage, biodiversity etc.) in perpetuity.

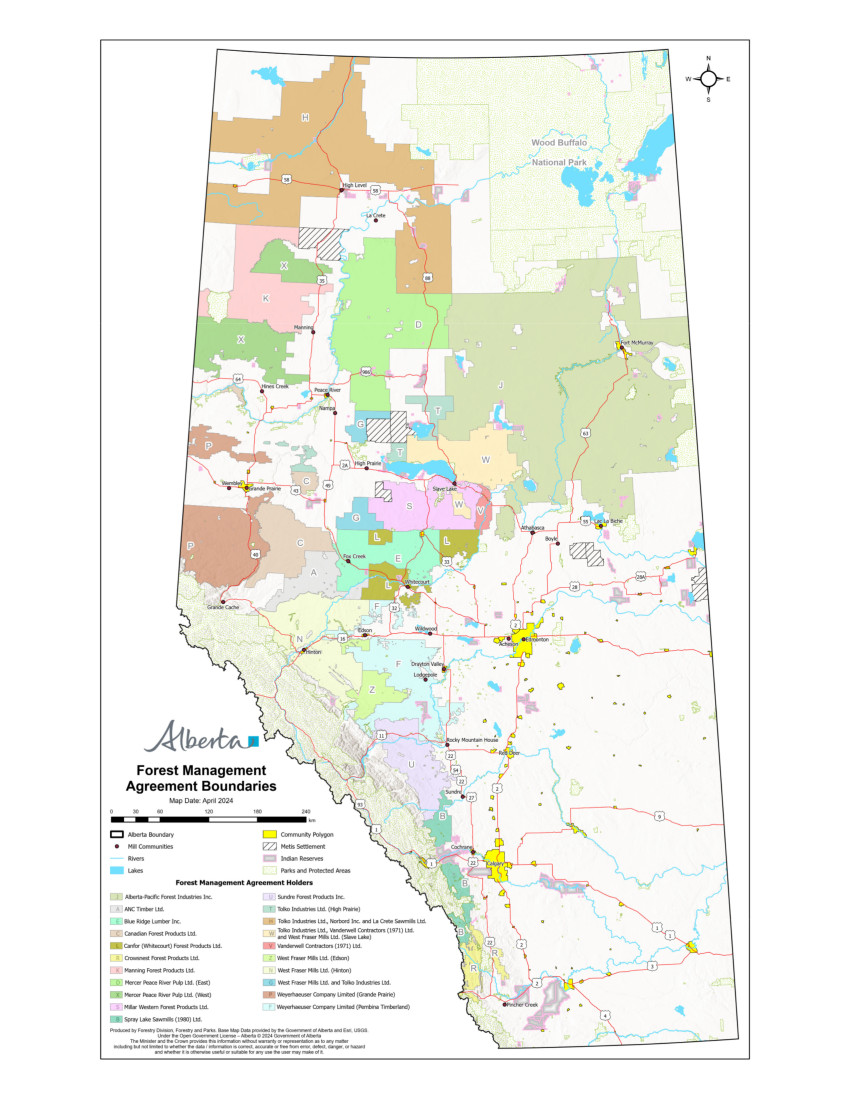

There are several avenues for forestry companies to acquire tenure on public lands, including timber quotas, timber permits, and forest management agreements (FMAs). FMAs are long-term, area-based tenure systems. The agreements last for 20 years before they are up for renewal, and give the FMA-holder the rights to establish, grow, and harvest a specified volume of timber in their area per year. The FMA-holder is also responsible for forest management planning in their FMA area. There is no public input required in the allocation of FMAs.

The inaugural FMA in Alberta was awarded to North Western Pulp and Power Ltd. in 1954. The company would build a pulp mill in Hinton, and gain a large tenure area in west-central Alberta, northeast of Jasper and east of what is now Willmore Wilderness Park. In the following decades, the solid wood sector would also expand, largely through the quota system rather than FMAs. It was only after the second FMA was signed in 1968 (by Proctor and Gamble Cellulose Limited, to build a kraft pulp mill in Grande Prairie) that environmental concerns with the forestry industry gained prominence.

In 1971, an environmental group called STOP took photographs in North Western Pulp and Power’s forest management area, which they published to show the lack of forest regeneration and the ecological destruction after harvesting. This prompted the government to hire a consultant to evaluate and report on the environmental impacts of forestry in Alberta. Their 1973 report kicked off the process that resulted in the 1977 Policy for Resource Management of the Eastern Slopes (hereafter the Eastern Slopes policy). The Eastern Slopes policy established zones with differing industrial and recreational land uses allowed to address competing land uses and protect watersheds. In recent decades, the management priority of watershed integrity in the Eastern Slopes has arguably been superseded to ensure a sustained supply of timber for the forestry industry.

Financial and environmental failures in the Boreal

An astounding expansion of forestry in Alberta was realized in the 1980s under Premier Don Getty. Due to crashing oil prices in 1986, and higher-than-normal unemployment rates, the government acted aggressively on a plan to diversify Alberta’s economy. This was a worthy goal, but came with many economic failures, and was at the expense of Alberta’s boreal forests.

Aspen, which accounted for a large proportion of boreal forest trees, was viewed as a weed until North American and Japanese pulp companies learned that aspen could actually produce more pulp than the hardwood species that had traditionally been used (and that were running out in many areas). The provincial government led a program to convince Japanese, American, and Canadian companies to invest in pulp mills in Alberta, and ended up handing out over $1 billion in assistance and loan guarantees over 18-months. This enabled Alberta to lease 221,000 km2 of public forests — nearly one-third of the land area in the province — to several companies from 1987 to 1988. Over two years, seven new pulp mill projects were announced. The requirement for public input on forestry projects was waived by the forestry minister of the time to encourage investment.

In addition, timber royalties were set extremely low to be competitive, which resulted in practically giving away public forests for free. Timber royalties are a price the company pays to the government to harvest trees that belong to the public. In 1989, Alberta’s timber royalties were said to be nearly the lowest of any jurisdiction in North America. When timber prices were low, the royalties may not have even been high enough to cover the costs of managing the agreements. This had been a concern before the expansion of forestry in the 1980s. As early as 1973, a government forest economist noted that the revenues that were being generated from the first two existing FMAs were much too low.

Some of the loans given out by the government in the 1980s turned out to be poor investments. One loan was awarded to Millar Western Pulp Ltd. in 1987 to help them construct a pulp mill in Whitecourt. In the decade that followed, none of the $120 million loan was repaid, and the government ended up writing off $272 million in exchange for a payment of $27.8 million. The Alberta Pacific Forest Industries (Al-Pac) pulp mill loan in 1991 was a similar failure. The three companies behind the project argued that they were unable to make interest payments on the loans they received, and in 1997 the government wrote off the $155 million owed in interest payments in exchange for the return of their initial loan investment.

Al-Pac’s pulp mill was extremely controversial from an environmental and public participation perspective. The proposed pulp mill would be built near the farming community of Prosperity, about a two-hour drive north of Edmonton, and would displace several families living there. Al-Pac’s FMA came with a large tenure in northeastern Alberta, spanning north of Lac La Biche to Wood Buffalo National Park and east of Highway 88 to the Saskatchewan border. Al-Pac’s FMA area is the largest in the province.

Pulp mills have a reputation for polluting the air and causing adverse health impacts to community members and mill workers, such as respiratory illness. Regardless, people living in Prosperity were not consulted on the mill proposal. When a farmer living in Prosperity raised the question of possible long-term impacts of the mill and the forestry operations on the community, Premier Don Getty responded that he had “no time for complainers.” The bleached kraft mill would release 900 litres of wastewater into the Athabasca river per second, chock full of harmful dioxins and furans. The test used by the company to determine whether their effluent would impact fish was to put fish in the wastewater and check if they were still alive four days later. Eighty percent of them lived, which apparently was good enough. Although many Indigenous communities rely on the Athabasca river for their livelihoods, they were nevertheless left out of plans for development of the mill.

The Al-Pac mill generated an unprecedented level of public opposition from residents of the area, Indigenous communities, academics, and people who were frightened by the rate at which forestry projects were moving forward in northern Alberta. Initially, the only opportunity for public input on the Al-Pac mill proposal came when an environmental impact assessment (EIA) for the mill was tabled, at which point folks living in Prosperity were given 16 days to comment on the 1,200-page report that was not written in accessible language. This brought to light serious problems with the EIA process, which did not meaningfully engage the public (the Canadian Environmental Advisory Council judged Alberta’s EIA process to be one of the weakest in Canada).

Public pressure relating to the Al-Pac mill proposal led the provincial and federal governments to launch a review board to assess the project and hold public hearings. The impacts of timber harvesting on public lands were considered out of scope of the review board, which would provide a recommendation to the Minister of the Environment because forestry operations were under the jurisdiction of the Minister of Forestry. The review board held public hearings in twelve locations, and ultimately recommended to the Minister of the Environment in March 1990 that the mill not be built until further studies could determine whether the project could proceed without serious impacts to aquatic life and downstream users. The review board also recommended that a thorough review of the FMA be carried out before the mill be approved. The minister initially accepted the recommendation not to approve the mill, until Al-Pac submitted a revised proposal that outlined mitigations to address concerns regarding chlorinated organic compounds. In December 1990, the government approved the project, even though the stipulated studies had not been completed (the government decided that studies could be done at the same time as the mill construction).

Where Are We Now?

The process of the provincial government signing away forests to private companies was rushed, secretive, and non-inclusive, which reflects the priority at the time of attracting investment. Forestry’s regrettable history of prioritizing access to timber above all else still underpins the industry today, although some requirements for public participation and environmental mitigations have been added on as an afterthought. The most recent FMA, signed in 2021 between the provincial government and Crowsnest Forest Products (a subsidiary of West Fraser), was signed without input from the public. This forest management area falls in the southern Eastern Slopes region, an area important for wildlife, watershed integrity and recreation. Today there is still no requirement for the public to be involved in the important decision of setting annual allowable cut levels (the decision about how much timber should be harvested from an area annually) or in the decision to renew a 20-year-long FMA. This makes it extremely difficult, if not impossible, for the public to stop clearcut operations in certain areas (e.g. for recreation or species at risk) because management control of the forests has already been signed away to a private company to extract timber.

Additionally, there is still no requirement for environmental impact assessments for logging operations. As seen with the case of Al-Pac described above, forestry companies only require an EIA for the construction of mills, and clearcutting operations are not considered in these assessments. This differs greatly from other industries that operate on public lands. A 1990 report prepared by the government Expert Panel on Forest Management in Alberta noted that “any EIA that covers only the impact of the pulp mill is inadequate and […] the impact of forest management practices must also be reviewed.” However, the panel report notes that the EIA process wouldn’t be able to adequately capture a “dynamic, evolving forest community,” and recommends instead that inclusive forest management advisory boards and review panels be established to address the need for environmental assessment of forestry practices.

As it stands, almost all of Alberta’s “Green Area” (forested area) that is commercially viable is under an FMA. Although these FMAs provide security to forestry tenure-holders, they don’t provide security for watersheds, species, or people. To usher in a new era of sustainable forest management in Alberta, some of these FMAs need to be reconsidered — particularly those in the Eastern Slopes headwaters, at-risk caribou ranges, and areas where Indigenous ways of life are, or could be, impacted. Smaller-scale, community-based forestry operations could replace large FMAs in certain areas that are compatible with forestry. This would place the management priority on ecosystems, people, and watersheds, while allowing forestry at sustainable levels that would benefit communities. At a time when healthy Eastern Slopes headwaters and boreal forest carbon sinks are more important than ever, changes in forest management are desperately needed.